Agnès Varda

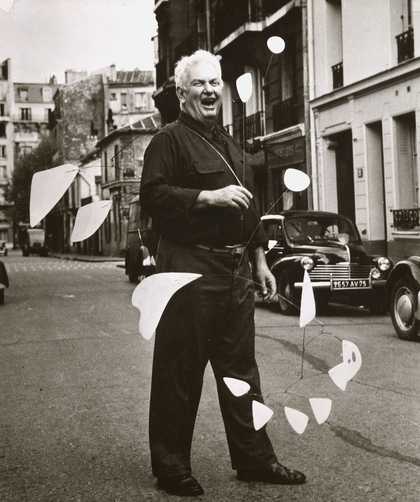

Calder with 21 feuilles blanches (1953), Paris, 1954

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Ã˝

Who is he?

Alexander Calder, known to many as ‚ÄòSandy‚Äô, was an American sculptor from Pennsylvania. He was the son of well-known sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder, and his grandfather and mother were also successful artists. Alexander Calder is known for inventing wire sculptures and the mobile, a type of kinetic art which relied on careful weighting to achieve balance and suspension in the air. Initially Calder used motors to make his works move, but soon abandoned this method and began using air currentsÃ˝alone.

Need to explain Alexander Calder to a kid? Head over to theÃ˝, for a simple and funÃ˝introduction..

Alexander Calder

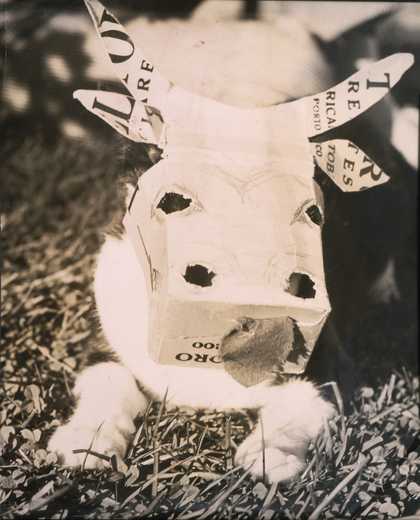

Cow mask for a cat, 1938

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Was he always an artist?

Calder always enjoyed making art. However, he trained as a mechanical engineer at the Stevens Institute of Technology in his early twenties. He began to pursue painting in earnest a few years after receiving thisÃ˝degree.

He is said to have chosen mechanical engineering arbitrarily, simply because someone he befriended was going to study that subject. Nevertheless he excelled at mathematics, and the experience was later applied to his unique and ingenious artisticÃ˝approach.

What is he most famous for?

Although not the first person to use metal and movement in his work, Calder became known for his pioneering use of both. In particular he was famous for what Marcel Duchamp christened, ‚Äòmobiles‚Äô, and what Jean Arp named ‚Äòstabiles‚Äô. Here, Calder explains the difference between the twoÃ˝terms:

The mobile has actual movement in itself, while the stabile is back at the old painting idea of implied movement. You have to walk around a stabile or through it- a mobile dances in front of you. (The Artist‚Äôs Voice, KatherineÃ˝Kuh)

Essentially his mobiles moved, often lacking the traditional base or pedestal which would usually anchor a sculpture to the floor. Stabiles were simply sculptures which were stationary and placed on the ground. These were often made on a colossalÃ˝scale.

Alexander Calder

Untitled, 1942

Gouache and ink on paper, 75.6 x 55.9 cm

Photo credit: Calder Foundation NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

How did this come about?

Calder visited Piet Mondrian‚Äôs studio in 1930, as described by himÃ˝here:

It was a very exciting room. Light came in from the left and from the right, and on the solid wall between the windows there were experimental stunts with colored rectangles of cardboard tacked onÃ˝‚Ķ.

I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate. And he, with a very serious countenance, said: ‚ÄòNo, it is not necessary, my painting is already veryÃ˝fast.‚Äô‚Ķ

This one visit gave me a shock that started things. (‚ÄòCalder‚Äô, Thames and Hudson, Ugo Mulas, H.H.Ã˝Arnason)

His response was to do what Mondrian refused to; make abstract artÃ˝move.

Alexander Calder

Cirque Calder, 1926–31

Whitney Museum

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Ã˝

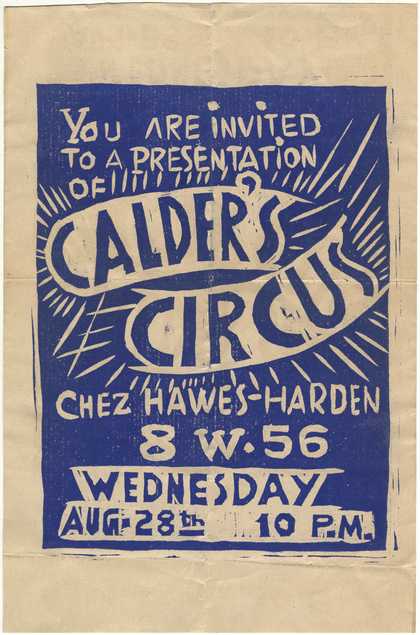

Alexander Calder

Invitation to a performance of Cirque Calder at the Hawes-Harden apartment, 28 August 1929

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

What was his favourite subject?

Calder loved the circus. In his twenties, whilst working at the National Police Gazette, he was asked to produce a series of illustrations of a circus troupe. As he later described in anÃ˝interview;

I love the space of the circus. I made some drawings of nothing but the tent. The whole thing of‚Äîthe vast space‚ÄîI‚Äôve always lovedÃ˝it.

When he moved to Paris in 1926, his interest quickly escalated into the creation of his own miniature Cirque Calder, fashioned from an array of found materials. He would pack this into two suitcases and give performances to his friends. Soon the two suitcases became five, and Calder began to make some modest earnings from the venture. As such, his career as an artist began in a very unusualÃ˝way.

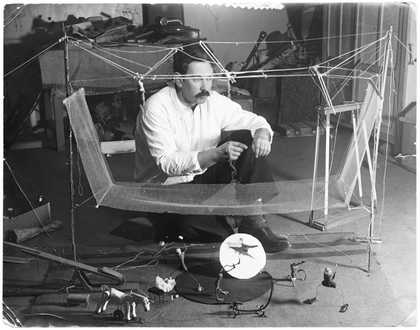

Sacha Stone

Alexander Calder with his Cirque Calder, 1929

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

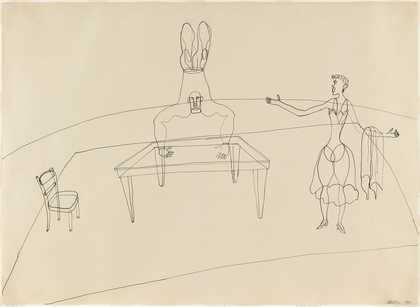

Alexander Calder

Untitled, 1932

Pen and ink on paper, 10 1/4 x 30 1/8 in.

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Was it all just fun and games?

His grandson, Alexander S. C. Rower, wouldÃ˝disagree:

In historical photographs, Calder often seems to be amusing himself in his workshop, Yet as those who had the rare fortune to be present in the act of creation can attest, Calder‚Äôs ‚Äúplaying‚Äù was actually the antithesis of frivolity. Calder‚Äôs instinctual experimentation resulted in an extended legacy, now loudly resounding in contemporary art of the twenty-first century. (‚ÄòCalder‚Äô, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Calder Foundation, Alexander S. C. Rower and TaeÃ˝Hyunsun)

Herbert Matter

Alexander Calder in his New York City Shorefront Studio, 1936

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

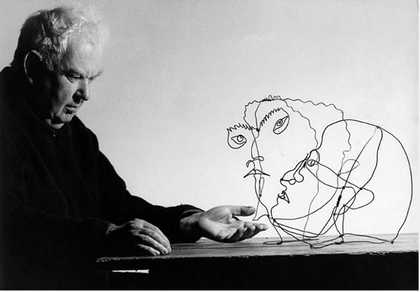

Ugo Mulas

Alexander Calder with “Edgar Varese” and “Untitled”, Saché, France, Gelatin silver print, 1963

Courtesy Ugo Mulas Archives

© Ugo Mulas Heirs

Artwork in photographÃ˝¬© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

What was his favourite drawing material?

Ã˝I think best inÃ˝wire

Calder always carried wire and pliers with him so that he could ‚Äúsketch‚Äù in his favourite material. This has come to be known as ‚Äòdrawing in space‚Äô because he would literally use the wire to create a drawing in theÃ˝air.

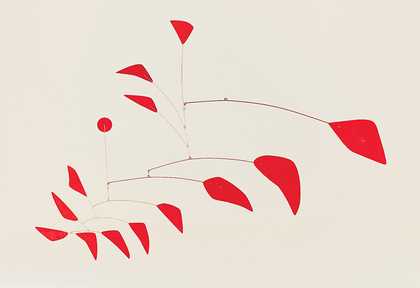

Alexander Calder

Big Red, 1959

74 √ó 114 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

What was his favourite colour?

It was probablyÃ˝red.

I want things to be differentiated [within my work]. Black and white are first‚Äîthen red is next‚Ķ It‚Äôs really just for differentiation, but I love red so much that I almost want to paint everything red. I often wish I‚Äôd been a fauve in 1905 (The Artist‚Äôs Voice, KatherineÃ˝Kuh)

Alexander Calder

Untitled (1937)

Tate

What were his thoughts on sculpture?

Calder avoided analysing his work, believing that: ‚Äútheories may be all very well for the artist himself, but they shouldn‚Äôt be broadcast to otherÃ˝people.‚Äù

As a result this poem-like text which he wrote for the Abstraction-Cr√©ation group magazine has often been taken as the closest thing to an explanation of hisÃ˝work:

How can art beÃ˝realized?

Out of volumes, motion, spaces bounded by the great space, theÃ˝universe.

Out of different masses, light, heavy, middling- indicated by variations of size or colour- directional line - vectors which represent speeds, velocities, accelerations, forces, etc‚Ķ-these directions making between them meaningful angles, and senses, together defining one big conclusion orÃ˝many.

Spaces, volumes, suggested by the smallest means in contrast to their mass, or even including them, juxtaposed, pierced by vectors, crossed byÃ˝speeds.

Nothing at all of this isÃ˝fixed

Each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go in its relationship with the other elements in itsÃ˝universe.

It must not be just a fleeting ‚Äúmoment‚Äù but a physical bond between the varying events inÃ˝life.

NotÃ˝extractions‚Ä®

ButÃ˝abstractions‚Ä®

Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting. (From Abstraction-Cr√©ation, Art Non Figuratif, no. 1,Ã˝1932)

Which are his key works?

Aside from Cirque Calder, which is universally loved, the following artworks are perhaps his mostÃ˝iconic.

Alexander Calder

Mercury Fountain in the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World's Fair, July 1937

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

In 1937 the Calder‚Äôs became very involved with the Paris World‚Äôs Fair, in particular the Spanish Pavilion. Calder offered to exhibit a mobile but initially the architect was against including a non-Spaniard in the show. However when they received a very plain looking fountain, which was to display liquid mercury from Almaden, they decided to call Calder in to create a new one. Calder‚Äôs Mercury Fountain was made of irregularly shaped steel plates for the liquid to run over, and also a rod with a red disc attached on one end, and the word ALMADEN written in wire hanging from the other. As the mercury moved through the fountain it would disturb the rod causing the disc and wire to oscillate in the air. The piece was shown alongside Picasso‚Äôs Guernica and entertained the audienceÃ˝greatly:

It became a favorite pastime of onlookers to throw coins at the surface of the mercury and see them float. (Calder: An Autobiography withÃ˝Pictures)

Ignorant of the fact Calder was actually American, Andr√© Beucler praised Spain‚ÄôsÃ˝accomplishment:

Spain has realized a masterpiece‚Ķ The exploitation of the mercury of Almaden is an important industry for Spain. There would have been many ways to make this theme tedious‚Ķ But, true artists, the Spaniards concentrated on one thing only: on the beauty of the mercury in its mysterious fluidity. (‚ÄòCalder‚Äô, Thames and Hudson, Ugo Mulas, H.H.Ã˝Arnason)

The piece can still be seen at Fundaci√≥ Joan Mir√≥ in Barcelona,but it is now displayed behind glass due to its highÃ˝toxicity.

Alexander Calder

La Grand vitesse, 1969

© 2003 Mary Ann Sullivan

In 1969, Calder‚Äôs monumental public artwork, his stabile Le Grande vitesse was installed in the plaza outside City Hall in Grand Rapids Michigan, USA. The title is a tongue-in-cheek French translation of the name ‚ÄòGrand Rapids‚Äô which also means ‚ÄòGreatÃ˝Speed‚Äô.

The artwork has caused great controversy from the word go. When locals discovered the plans there was a hot debate in the local newspapers about whether the project should go forward. Even to this day many people do not appreciate Calder‚ÄôsÃ˝vision.

Nevertheless the Plaza has become known as Calder Plaza, and there is an annual arts festival on the artist‚Äôs birthday. Le Grande vitesse is even seen on street signs and the city government letterhead, placing the artwork at the heart of the city‚ÄôsÃ˝identity.

How did he transport some of his artworks?

Calder developed the idea of dismantling even large sculptures so they could be posted unobtrusively avoiding customs problems. He essentially designed flat pack artworks. He would also send detailed numbered and colour coded instructions along with the piece so that it could be reassembled correctly on the otherÃ˝end.

Alexander Calder

Untitled, 1959

Sheet metal, wire, and paint, 7 1/4 x 6 1/2 in.

Private Collection, San Francisco

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, NY/ Art Resource, NY

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

What do the critics say?

Jean-Paul Sartre on Calder‚Äôs mobiles: ‚ÄúThe forces at work are too numerous and complicated for any human mind, even that of their creator, to be able to foresee all their combinations. For each of them Calder establishes a general fated course of movement, then abandons them to it: time, sun, heat and wind will determine each particularÃ˝dance.‚Äù

‚ÄúOne cannot describe his works- one must see them‚Äù said separately by Bruno E. Werner, ‚ÄòPortraits, Sculpture, Wire Forms,‚Äô Nierendorf Galerie, Deutsche, Allgemeine Zeitung, April 1929 and by E. Szittya, ‚ÄòAlexander Calder‚Äô, Kunstblatt, JuneÃ˝1929.

‚ÄúThere is an element of the piper of Hamelin‚Äôs tune in the purring and jigging of a roomful of his ‚Äúmobiles‚Äù that calls the child out of us in spite of ourselves‚Ķ In a roomful of Calder‚Äôs we are conscious of a definite heightening of vitality‚Ķ‚Äù (James Johnson Sweeney, ‚ÄòAlexander Calder‚Äôs Mobiles‚Äô, from Mobiles by Alexander Calder. exh. cat. (Chicago: The Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago,Ã˝1935)