Charles MartinPortrait of John Martin on his deathbed┬Ā1854Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle

Follow the link for ┬Ā and youŌĆÖll find an image of Leonardo, with a caption which tells us that he is ŌĆśone of the most recognizable polymathsŌĆÖ. John Martin doesnŌĆÖt even make it onto the long-list of historically notable multi-taskers. But this wasnŌĆÖt for want of trying on the artistŌĆÖs part. Although John Martin is best remembered today as the painter of apocalyptic bibical scenes, by his own account he dedicated something like two-thirds of his time and huge amounts of money to developing increasingly ambitious engineering schemes. From the end of the 1820s until the last few years of his life (he died in 1854), John Martin published a succession of detailed plans and written proposals for transforming LondonŌĆÖs sewerage and transport systems. Although his schemes were taken seriously at the highest level, none of them got off the ground in the way Martin envisaged. Rival business interests blocked his plans, and his proposals were sometimes dismissed outright as ŌĆśBabylonishŌĆÖ visions. His reputation as a painter of wildly imaginative scenery didnŌĆÖt┬Āhelp.

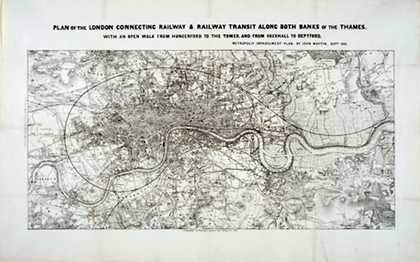

In retrospect, MartinŌĆÖs plans can look as ŌĆśvisionaryŌĆÖ as his paintings, as if he was planning to give modern, industrial form to the much-vaunted heavenly ŌĆśNew JerusalemŌĆÖ which many Britons expected to see rise in their own time. He imagined the embankment of the Thames, something which took place (giving the riverfront its familiar appearance) only after his death. And he proposed a circular railway line, which ran from the east of London, across what was then northerly suburbs (it would have run just north of Regents Park) through the open fields to the west (again, now built-up, central London) and across the south (connecting with Vauxhall), out to Greenwich. ┬ĀAs so often with Martin, he felt that his ideas were pilfered by other parties, in this case the Metropolitan Terminii Commission who at the same time as Martin published his proposals came up with their plan for encircling central London with terminal railway stations and barring steam trains from coming into the centre of┬Ātown.

Plan of the London Connecting RailwayŌĆ”┬Ā1845From the collection of Michael J. Campbell

As the scholar Lars Kokkonen explores in his essay for the catalogue accompanying John Martin: Apocalypse, the idea that Martin was inspired to come up with these engineering plans from religious feelings doesnŌĆÖt really hold up. He wasnŌĆÖt a religious eccentric or rebellious outsider as if often assumed. The pollution of the Thames and the problems with LondonŌĆÖs transport infrastructure were pressing issues in John MartinŌĆÖs day, and like many others he saw that coming up with proper solutions could be a route to making a fortune. His dedication to civil engineering was another aspect of his commercial outlook. Lars Kokkonen and the print specialist Michael Campbell discovered independently that Martin was an exhibitor at the Great Exhibition in 1851, and I found out that he was able to make some money at the very end of his life from a patent he was granted for ŌĆśImprovements in Apparatus and Means Used in Draining Cities, Towns, and other Inhabited Places and LandŌĆÖ. But at the same time, John Martin seems to have invested far too much in these schemes for this to have been the result of purely rational self-interest. He seems to have been driven by something other than commonsense or cynicism, as much with these engineering proposals as with his grandiose and always controversial art. His impoverished background, and lack of education and training may have led him to invest too much (time, money, energy) in enterprises which promised to secure him social prestige, fame and money: he was trying too hard to impress,┬Āperhaps?