Photographer Unknown

Black and white negative, Paul sketching [Whiteleaf?]

TGA 7050PH/869Ìý

At the outbreak of war, Paul Nash enlisted in the army and he was posted to Ypres in Belgium in early 1917, but after an injury from a fall, returned to England a few months later. He was keen to become an official war artist, writing in July that he was ‘… prompted by an idea and goaded on by John [his brother] from behind…’ to enquire about ’ … a permit or a special licence to draw in the ‘line’ and facility for seeing all the different sectors …’ (IWM: ART/WA1/294/1).Ìý

First World War correspondence between Nash and the Ministry of Information reveals how he also gathered influential supporters for his appointment as official warÌýartist.Ìý

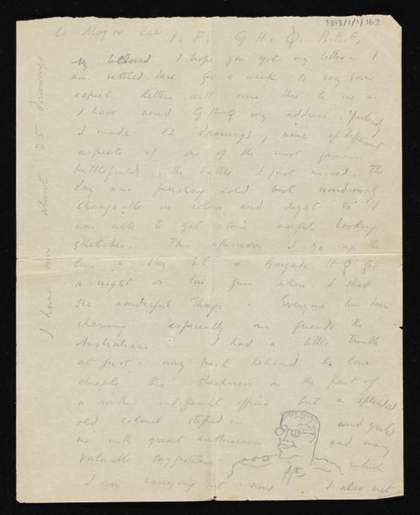

However, after arriving at the front line in France the letters to his wife Margaret take on a very different tone. By then Nash had seen the devastation of the War. In November 1917 heÌýwrote:

Letter from Paul Nash to Margaret Nash written from France while on commission to make drawings at the Front as a war artist

13 November 1917

TGA 8313/1/1/162Ìý

… I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousyÌýsouls.

The IWM Archive also contains Nash’s reports about his activities and evidence of the Ministry’s efforts to place reproductions of his war work in magazines, ostensibly for propagandaÌýpurposes.

The British Artists at the Front was one initiative focused on bringing the work of war artists to a ‘middle-class’ audience. The series was published by Country Life, and volume 3 was dedicated to PaulÌýNash.

British Artists at the Front: Volume 3Ìý

© IWM

Produced in 1918 and showing works from 1917. The publication has an introduction to the artist, written by John Salis, and full page reproductions of Nash’s works withÌýcaptions.

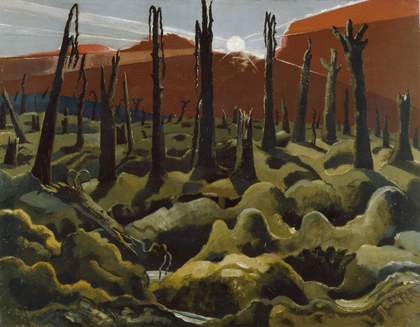

The work featured on the cover of volume 3 of British Artists at the Front was Nash’s painting . The title mocks the ambitions of the war, as the sun rises on a scene of total desolation. However, this ironic title did not appear anywhere in theÌýpublication.

Paul Nash

We are Making a New World 1918

Oil on canvas

© IWM (

Despite its anti-war sentiment, Nash’s war work at this time received a good public and critical reaction. Unlike his contemporary CRW Nevinson, Nash escaped censorship, partly because the official censor did not understand how ‘Nash’s funny pictures’ could give any information to theÌýenemy.

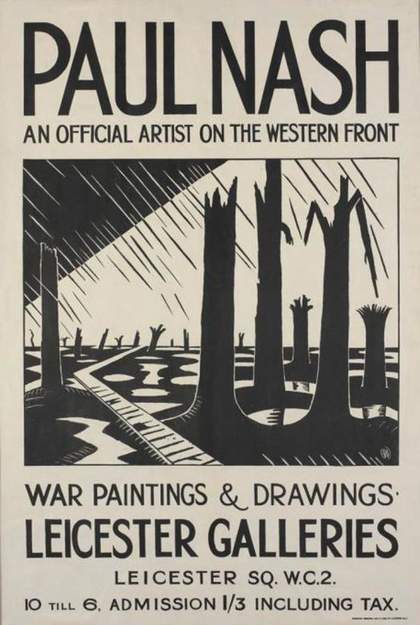

We are Making a New World was the most acclaimed work in Nash’s 1918 exhibition Void of War. Held at the Leicester Galleries, the works revealed the damage caused to the landscape on the Western Front. Nash equated this destruction of nature with humanÌýdevastation.

Poster for Void of War exhibition 1918

Ìý© IWM (Art.IWM PSTÌý3513)

The IWM War Artist Archive file ART/WA1/295 also contains the Void of War invitation and pressÌýcuttings

In 1918, Nash was one of several artists commissioned to create a large painting by the British War Memorials Committee for a new scheme to create a grand ‘Hall of Remembrance’. It was to be filled with paintings by British artists that were devoted to ‘fighting subjects, home subjects and the war at sea and in the air’. ÌýNash produced The Menin Road (1919), which was originally to have been called ‘A FlandersÌýBattlefield’.Ìý

Paul Nash

The Menin Road 1919

Oil on canvas

© IWM ()

Official papers relating to the British War Memorials Committee reveal that Nash suggested the following inscription for theÌýpainting:

The picture shows a tract of country near Gheluvelt village in the sinister district of ‘Tower Hamlets’, perhaps the most dreaded and disastrous locality of any area in any of the theatres of War.(IWM: ART/WA1/490-525)

The Hall of Remembrance scheme was intended to provide a permanent artistic memorial to the First World War in Britain. Other artists commissioned included John Singer Sargent, Wyndham Lewis and Stanley Spencer. However, at the end of the First World War the Treasury forced the closure of the scheme, and the paintings were transferred to IWM.

Nash became an official war artist once again in the Second World War, and developed a particular fascination with the idea of aircraft as central characters in the War. This reflected his interest in surrealism, which had developed during the interwar years. In an article written for Vogue in 1942 titled ‘The Personality of Planes’, he explained his anthropomorphic vision of these machines. Through a placement with the Air Ministry, Nash was able to observe planes up close, both static and taking off from the runway. However, due to his asthma it is likely he never flewÌýhimself.

Paul Nash

Black and white negative, aeroplane parts, Cowley Dump 1940

TGA 7050PH/68

Nash surrounded himself with photographs of these ‘beautiful monsters’, becoming familiar with the characters of the different British war planes. He also took many photographs of wrecked German aircraft at Cowley dump, which he used as source material for his painting Totes Meer (1940–1). ‘Totes Meer’ is German for ‘Dead Sea’. Nash envisaged the piles of salvaged German aircraft as a sea of dead creatures, which seemed to him to pitch and churn when bathed inÌýmoonlight.

Paul Nash

Totes Meer (Dead Sea) (1940–1)

Tate

Totes Meer also provides a great example of how exploring archival material alongside his paintings can provide a deeper understanding of Nash the artist and the man. With its depiction of defeated Nazi bombers amid the Blitz years, it was intended to boost patriotic sentiment. However, its melancholy air also suggests another more personal interpretation, centring on Nash’s relationship with the artist Eileen Agar. The affair had ended some years before the War, but Nash continued correspondence with Agar. His letters in the Tate Archive reveal how Nash likened their love to flight, and the comparison of the end of the relationship with a sea of grounded aircraft is compelling (see Eileen Agar archive, Tate: TGAÌý8712).

Paul Nash’s paintbox and painting equipment

© Tate archive

The Tate Archive is an excellent source of material on Paul Nash, and much of it is available online. Tate holds his letters and papers, which include correspondence with Margaret Nash (c.1894–5 November 1951: reference TGA 8313) and texts written by Nash for catalogues and periodicals on specific war paintings, and on art and war. Tate also makes available online a set of photographs taken by Paul Nash, which he would often use as source material for his paintings (TGA 7050PH).Ìý

has the official First and Second World War documents and correspondence relating to Nash (ART/WA1/294/1 and 2, ART/WA2/03/043/1 and 2). These can be viewed on microfilm through an IWM Research RoomÌýappointment.

Paul Nash is at Tate Britain until 5 March,Ìý2017.

See Paul Nash’s work, alongside over 300 objects in from 27 March – a major exhibition at IWM London exploring how peace movements have influenced perceptions of war andÌýconflict.