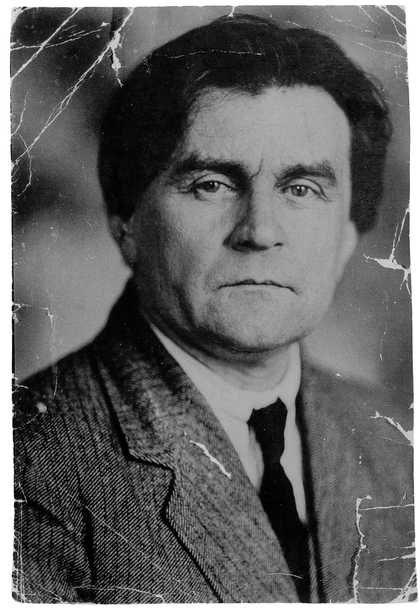

Photograph of Kazimir Malevich, c1925

漏 State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New聽York聽

Early twentieth-century Russian painting innovators followed in the wake of their Western contemporaries鈥� artistic discoveries, but they strove passionately for independence and originality. The breakthrough was made by聽Kazimir Malevich, who first created wholly abstract compositions. His most famous work,听Black Square聽1915, became a universal symbol of a new era in聽art.

A few words about the artist鈥檚 biography: according to new information, Malevich was born not in 1878 but in 1879, in Kiev, to a Polish family; he died in Leningrad in May 1935 from a serious illness that prevented him working during the last year of his life. He did not emerge as an avant-garde painter until 1910, when he was over 30, meaning that his career spanned only a little more than two decades. During this brief time, Malevich was effectively an entire contingent of artists, each of whom had the first or definitive word in many spheres of artistic聽culture.

In painting, any one of Malevich鈥檚 artistic periods after 1910 - be it his first series of paintings of agricultural workers, his Expressionist Neoprimitivism, or Cubo-Futurism - would have guaranteed him a place of honour in the history of Russian art. While everything that happened in 1913 and afterwards - his set design for the聽Futurist听辞辫别谤补听Victory Over the Sun, the alogical painting of what he called Fevralism,听Suprematism, the 鈥榩lanits鈥� [Malevich鈥檚 idea of man-made planets], his visionary architectural models the 鈥榓rchitectons鈥�, the post-Suprematist painting - each on its own would have secured him an unrivalled place in the history of world聽art.

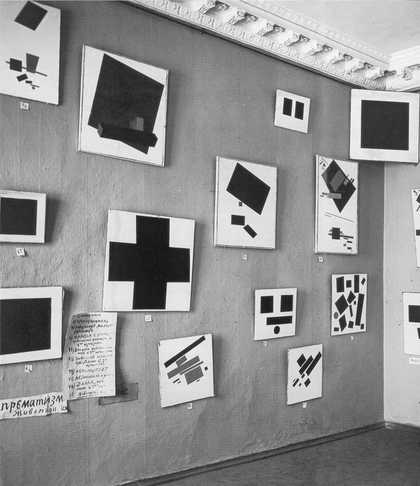

Installation view of Kazimir Malevich's paintings at 'The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0:10', Petrograd, 1915

Collection Charlotte Douglas, New York, courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York聽

It was his work on聽Victory Over the Sun聽that gave rise to his first personal 鈥榠sm鈥�, Alogical Fevralism. Speaking at a debate in February 1914, the artist announced that he had 鈥榬ejected reason鈥�. The Fevralist was now placing his bets on irrational 鈥榮ensation鈥�. Freed from objective representations, this would lie at the heart of the new art and, through it, a new world view, and could rest only on phenomena that were purposely not subject to the distorting directives of human reason. Malevich, born the same year as Albert Einstein (1879-1955), perceived these phenomena in physical manifestations such as electricity, R枚ntgen rays and gravitation, which reigned invisibly in space and聽time.

In spring 1915 the solar symbolism of聽Victory Over the Sun聽took on new meaning for Malevich. In addition to its 鈥榙esconstructivist鈥� (his own term) objectives, the Futurist masterpiece was discovered to have utopian-constructive potential, which the painter linked to the energetic essence of universal processes and their invisible incorporeal might. Henceforth, the Russian avant-gardist would consider embodying nature鈥檚 true (read, abstract) being to be the goal of both his own art and art as a聽whole.

Malevich included the expression 鈥榩artial eclipse鈥� in his works during his Fevralism period, such as聽Composition with Mona Lisa聽1914. The聽Black Square聽of 8 June 1915 marked the 鈥渢otal eclipse鈥� that had long been maturing in his art. The black rectangular plane definitively crowded out the natural celestial body that had ensured the sensory perception of earthly reality. It shifted its creator to another - purely speculative - dimension. 鈥楢 system is being constructed in time and space; independent of any aesthetic beauties, experiences, moods, rather [it] is a philosophical colour system for realising the new achievements of my ideas as cognition,鈥� Malevich wrote in the preface to a 1919 group exhibition in Moscow. Subsequently, in his theoretical works he expanded several times on the unitary nature of the universe鈥檚 spaces and 鈥榯he infinite space of the human聽skull鈥�.

Malevich called his abstract compositions Suprematism, which in its first stage meant the dominance of colour energy and its transformations in painting. For him, the life of colour as such was indissolubly linked to the universe: object-less colour generated the sensation of its object-less, image-less聽being.

According to Malevich, the 鈥榳hite abyss鈥� of the background, whose whiteness was conditioned by the extreme incandescence of energetic tension in the universe, was the manifestation of space on Suprematist canvases. In late 1917 the painted elements became increasingly dynamic. Their sharp edges cut into the whiteness, and as the concentration of colour decreases, the boundary between figure and background聽disappears.

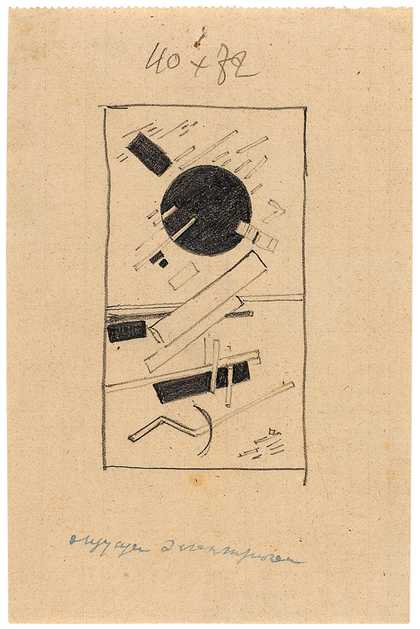

Kazimir Malevich

Composition 14t (Suprematism: Sensation of the Electron) 1916听

Graphite on paper, 154 x 100mm

Collection of Kharzhiev Foundation, Amsterdam聽

Malevich called this process 鈥榙issolution鈥�, a term with cosmic connotations: 鈥楾he cosmos is dissolution. The Earth is a small splitting,鈥� as AA Leporskaia quoted her teacher in her diary. Through the dissolution of colour by the white abyss in Suprematism, the phenomenon of non-material time, linked to non-figurative space, appeared more often. In a 1918 poem, Malevich developed this聽idea:

Each shape has a real type of time and the coloration of colours is the power of the time鈥檚 oscillation, time鈥檚 movement creates shape while simultaneously colouring it and consequently the speed of time can be defined by聽colour.

尝颈办别听Black Square聽before it,听Suprematist Composition: White on White聽1918 was created over an existing painting. The white square on the white background was a symbol signifying the move of an author transformed by transcendence into the 鈥渨hite world聽order鈥�.

In Malevich鈥檚 everyday life, his proclamation of the inevitable break from earth and speculative mastery of space turned into a passionate immersion in astronomy. During his Vitebsk years (1919-22), he was never parted from his pocket telescope, constantly observing and studying the starry sky, the map of which he knew thoroughly. This engendered one of his most astounding texts,听Suprematism: 34 Drawings, published on 15 December 1920 with its prophetic lines in the introduction about humanity鈥檚 cosmic future. It was here that he gave the ordinary word 鈥榮putnik鈥� - Russian for companion or fellow traveller - the meaning that made it famous. As we know, 鈥榮putnik鈥� has existed in all the world鈥檚 languages without translation ever since the call signs of an artificial, man-made celestial body went out on 4 October聽1957.

In his text, Malevich lays out visionary ideas of amazing heuristic power, while touching on a sphere seemingly removed from art -聽technology:

The Suprematist machine, if it can be put that way, will be single-purposed and have no attachments. A bar alloyed with all the elements, like the earthly sphere, will bear the life of perfections, so that each constructed Suprematist body will be included in nature鈥檚 natural organisation and will form a new sputnik; it is merely a matter of finding the relationship between the two bodies racing in space. A new sputnik can be built between Earth and Moon, a Suprematist sputnik equipped with all the elements that moves in an orbit, forming its own new聽path.

In these last words one cannot help but recognise the space stations so familiar to us today, which truly are 鈥榥ew sputniks equipped with all the聽elements鈥�.

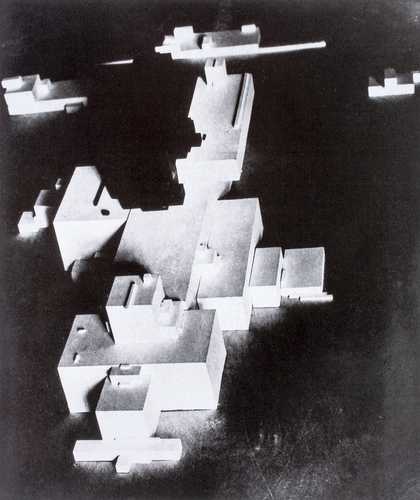

Photograph of one of Kazimir Malevich's architectons, Beta c1920

Courtesy State Russian Museum, St Petersburg

Malevich goes on to propose a scheme for overcoming gravitation between celestial bodies and ensuring progressive advancement into the cosmos: 鈥楢fter studying the Suprematist shape in motion, we have decided that movement in a straight line towards any planet can only be accomplished by the annular movement of intermediate Suprematist sputniks forming a direct line of rings from sputnik to sputnik.鈥� Then come lines that make us think that the artist had peered into the distant future: 鈥業n my research I discovered that Suprematism holds the idea of a new machine, i.e. a new, wheel-, steam- and gasoline-less engine of the聽organism.鈥�

For many years, Malevich the theoretician used astronomic terms while studying the culture of contemporaneity. Tools borrowed from the astronomic discourse seemed to bolster and strengthen the strict universal law that he believed served as the foundation for artistic creation. The great generator of plastic ideas labelled his architectural models, or architectons as they were called, with Greek letters the way astronomers label the constellations. His architectons (alpha, beta, zeta) were also the earthly precursors of a new architecture; they were supposed to be transformed into 鈥榩lanits鈥� - installations soaring into space and inhabited by 鈥榚arthlings鈥�. 鈥楶lanits for earthlings鈥� were on a par with the planets and stars in the universe. The designs and neologisms Malevich created for them neatly accentuated Suprematism鈥檚 cosmic聽vector.

The Russian avant-gardist was not only a great artist, he was also a keen thinker and subjected recent movements -聽Impressionism,听Cubism,听Futurism聽- to theoretical research. These were all retrospective analyses, as he strove to understand the sources of his own achievements in art. But he was fated to know only in part what he had created, produced and engendered in his own lifetime. The entire twentieth century would go on displaying things that came into the world via Malevich in new contexts and聽interpretations.

Many phenomena that appeared for the first time in his work were only picked up on years later. For example, people have quite rightly seen the simple, singular shapes of the Suprematist protofigures as harbingers of the aesthetics of minimalism in the second half of the century, while his white on white canvases resonate, for example, in the monochrome works of聽Yves Klein. His true recognition did not come until the 1960s, but the discoveries that brought fame to his successors already existed in the Russian鈥檚 work, seemingly having settled for the time being in the collective artistic聽subconscious.

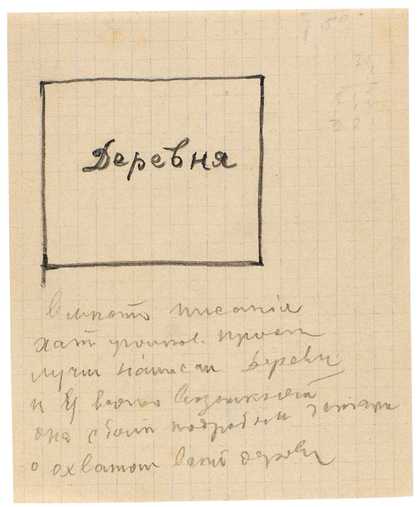

Kazimir Malevich

Alogmisme 29. Village 1913-4听

Collection of Khardzhiev Foundation, Amsterdam聽

A drawing not made public until 2000 shows us that Malevich created an extremely mature Conceptualist work. Writing the word 鈥榁illage鈥� in a frame, he explained: 鈥業nstead of drawing the huts of nature鈥檚 nooks, better to write 鈥榁illage鈥� and it will appear to each with finer details and the sweep of an entire聽village.鈥�

His first one-man show, 鈥楰azimir Malevich: His Path from Impressionism to Suprematism鈥�, opened in Moscow on 25 March 1920. Following the white on white works, it ended with empty canvases that seemed to hurl man into the space of pure speculation, standing him in front of a clean screen on which he was free to project his own ideas within the broadest聽range.

The artist-philosopher was bewitched by 鈥榚mptiness鈥�, which contained everything and spoke of the presence of the Absolute (God). He expressed his astonishing intuition as well in about 1924, on the clean flyleaf in his notebook, where a line appeared: 鈥榯he goal of music is silence鈥�. It鈥檚 hard to get away from the thought that聽John Cage, who in 1952 created his famous silent opus 4鈥�33鈥�, found an extraordinarily effective way to realise this idea, which was, in fact, a favourite notion of the twentieth-century arts in general. However, Malevich was able to embody it more than once, and by quite various means, which in and of itself speaks to the great inventiveness of his talent. For his聽Black Square聽was the Zero of forms, his empty canvases were the Zero of forms, and his 鈥榯he goal of music is silence鈥� was the Zero of聽forms.