Ed Atkins

The worm 2021

Video still

© Ed Atkins. Courtesy the artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

Ed Atkins says his work is 'steeped in an involuted figuring with death’. Aren’t we all? Young artists often avoid the subject of death. It’s out of range. They look outward for their subjects, at formal problems or current affairs that press at them from the world. They live for art but have not yet invented themselves. Then middle age arrives bearing gifts of backache, balding, menopause. Death looms. The artist turns inward and finds vast storerooms full of material. They note that more life lies behind than ahead.

It begins to seem important for the artist to find a narrative thread that connects the things they’ve done: ‘When I was young,’ said Francis Bacon, ‘I needed extreme subject matter for my paintings’ – demagogues, screaming popes, figures in tortured isolation – ‘then as I grew older I began to find my subject matter in my own life.’ He painted his friends and, when they died, an increasing number of self-portraits. When the art critic David Sylvester asked why, Bacon replied: ‘I loathe my own face, but I go on painting it only because I haven’t got any other people to do.’ He quoted Jean Cocteau: ‘Each day in the mirror I watch death at work.’

Atkins is in his early forties and you can see his preoccupations in his face. He draws self-portraits: close-cropped, unsparing forensic accounts of his wrinkles, nose hairs, eye bags and crow’s feet. In some, his poses appear corpse-like, modelling for the pathologist’s slab. Or maybe it’s the analyst’s couch? That would make sense of the drawings in which he gives himself the body of a spider, as if to express a sense of self-revulsion, even threat. I hear strange echoes of Bacon and Cocteau when Atkins says in a recent interview with curator Polly Staple: ‘I loathe my body and the way I look. I am often entirely destroyed by an encounter with an image of myself.’ But then, as musician Robert Wyatt once sang: ‘What kind of spider understands arachnophobia?’

Ed Atkins

Copenhagen #6 2023

© Ed Atkins. Courtesy the artist and Cabinet Gallery, London

The 3D-model figure in the video Pianowork 2 2023 bears a remarkable likeness to Atkins. ‘It’ or ‘he’ – we’ve hit an interesting ontological wrinkle here – sits at an upright piano in a dark space, wearing a white shirt, black sweatshirt and trousers, and scuffed leather shoes. An artist with a dash of school uniform. As with Atkins’s drawings, the detailing is excessive: each root of the salt-and-pepper hair, every pore and beard bristle is accounted for in high resolution. A cold light from offstage brings out faint creases in the avatar’s forehead and shows up tiny, red blotches against his pale cheeks. A pair of small, gold earrings look extra hard at the point where they pierce his soft lobes. Sometimes there is a close-up of his hands. One finger looks rubbery. Something in the figure’s posture seems weightless, boneless – with nothing inside that obeys gravity, nothing that could push a piano key down.

He’s playing ‘Klavierstück 2’, a minimalist piano piece by Jürg Frey: quiet chords separated by lengthy pauses which the performer has to silently count off. The avatar’s movements were motion captured while Atkins played the piece himself, heightening the sense of feeling behind the performance. Muscles twitch around the avatar’s mouth, his expression seeming to signal when he’s counting the beats or deliberating where to place his fingers next. He’s trying hard to get it right. Occasionally a little crinkle around the eyes suggests enjoyment. He’s aiming for an evenness of pressure and tone on each chord but not always managing it, and he flashes a little squib of a smile – perhaps one of self-reproach – to mark a mistake that only he noticed.

In a novel or film it’s often a small but specific observation of speech or behaviour that brings a character to life. But a successful story is one that leaves space for the audience to fill in the blanks. Too much effort to make a person come alive – too much data – paradoxically deadens the portrayal. Bacon said he wanted to show ‘all the pulsations of a person’ in his painting – pulsations being whatever life force he saw in his subject. His method involved throwing great fistfuls of paint at the canvas, smearing and scraping it, trying to imbue it with movement and mutability. Atkins captures these pulsations too. But the hyperrealism of his animated models makes them seem alien. We don’t register every hair and skin bump when we look at someone. The mind applies a perceptual glue to what it sees, hears, feels; a softness, a blurring almost, of perception, assessment and memory. Atkins takes advantage of a paradox in the technology, showing how – in the pursuit of fidelity, in achieving the most realistic depiction of a zit on someone’s forehead – it fails to capture the beautiful mystery of seeing and being.

Ed Atkins

Pianowork 2 2023

Video stills

© Ed Atkins. Courtesy the artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

Ed Atkins

Pianowork 2 2023

Video stills

© Ed Atkins. Courtesy the artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

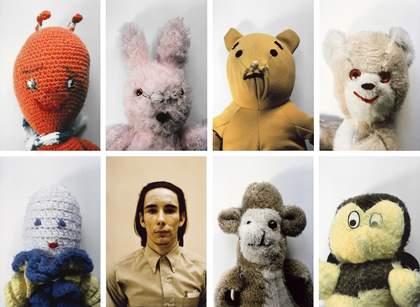

Atkins’ avatars are generally off-the-shelf models: men or boys that can only walk or talk stiffly, limited by a realistic but narrow range of movements. (A joke about all men is begging to be made there.) The models are edging obsolescence. In the Atkinsverse, you might take this as a metaphor of ageing: the out-of-date avatar is the irrecoverable body, something that was once useful, desired, but now past it. Their faces are videogame bland, but Atkins afflicts them with a skin disease or makes their eyes look red and puffy, as if they have suffered some unidentified emotional wobble. In Good Man 2017, the model is dressed like a character from Game of Thrones, all fantasy medieval – leather hood and lace-up jerkin – weeping into a guttering candle in rain-soaked darkness. His skin looks scabbed and sore. The set-up has all the components of a dramatic scene and teases with the promise of a story, but the narrative never arrives. You wonder if this feeling of stasis is what the figure is crying over. He’s dressed for heroism but is emotionally paralysed.

These video pieces remind me, oddly, of Renaissance anatomy drawings. The physician Vesalius, in his 16th-century anatomy atlas, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Of the Structure of the Human Body), published engravings of flayed bodies walking through Arcadian landscapes, skeletons leaning casually against ruined pillars or idly toying with a skull like a child playing with a ball. The illustrations were designed to provide information about how bones connect to musculature, what routes the nerves take from the brain stem, how the body looks in motion. Atkins’s 3D models aren’t doing quite the same thing, but the degree to which they try to reproduce the look and feel of a body in microscopic detail seems connected. His figures are the walking dead, like the Vesalius skeletons. You could imagine the avatars and the anatomy drawings in search of similar metaphysical treasure, attempting to find out how the heart works both as mechanical pump and a source of love, sadness, desire. A religious person would call this animating energy the soul. A modernist would call it consciousness.

Atkins is the author of three books: A Primer for Cadavers (2016), Old Food (2019) and Flower (2025). Inventive, funny, confessional, they read like 21st-century descendants of the novels of James Joyce or Virginia Woolf with their detailed maps of the mind in motion. Atkins is an enthusiastic list-maker. Flower, for instance, reads as stream-of-consciousness observations pulled from a vast, emotional memory catalogue. For example, he’ll start with clammy sandwich wraps, narrating in detail the reasons why he likes them, how they feel in his mouth – the descriptions spiralling outwards into something between a Proustian reverie and a cosmic scream of despair: ‘The best wraps all taste the same: sweet creamed hospice. The wraps I like are best and look like these spent prophylactic alien larvae props. I push them through my mouth.’

Ed Atkins

Good Man 2017, part of Atkins’s installation Old Food at Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf in 2019, in which it is displayed alongside monumental clothing racks hung with opera costumes from the Deutsche Oper Berlin

© Ed Atkins. Photo: Achim Kukulies, Düsseldorf

In The worm 2021, Atkins turns from the self to the family. The video is set in a TV studio suffused with soft, magenta lighting. This time, the double is clean-shaven, 30-something, dressed in a smart, checked suit. The avatar looks nothing like the artist. But somehow, we know it is Atkins. He sits in a chair, beside him a glass Eileen Gray table with a crystal tumbler, an ashtray and a pack of Silk Cut cigarettes. The suit and props suggest maturity, success and good taste but seem to be doing a lot of lifting for this character.

The avatar is here to talk to his mother, or rather, Atkins is here to talk to his mother. (Atkins says the real conversation behind this piece was difficult but that both parties did it from a place of love. This sincerity shines through.) His mother’s voice emanates from a phone or laptop, playing over invisible speakers in the studio. It sounds tinny, while the digital double’s voice is deep and close – a subtle suggestion of a power imbalance. Atkins’s mother talks about her childhood, about insecurity and emotional inheritance. The double listens intently, making the little noises people make to signal that they’re paying attention – ‘uh huh’, ‘yeah’, ‘mm’ – offering the occasional leading question and suggesting a break when the emotion becomes too much for either of them to bear.

The audio track of the conversation is naturalistic. It carries a real sense of gravity and moral consequence in contrast with the weightless avatar, who never quite looks realistically situated in space. Recognising a sound when you can’t see what’s making it usually involves identifying a physical material too – metal, wood, plastic, breath, a body – and the voices in Atkins’s film have an implied solidity to them, a raw truth, that rubs against the weightlessness of what we’re seeing.

The worm is both moving and uncomfortable to watch. Is this an analysis session? A confessional? Is it even meant to be public? The studio setting – and the fact that we’re watching it in a gallery and you’re reading about it in a magazine – says, of course, this is public. It could even be one of those reality TV shows about therapy. Who the public is, and in whose interests this conversation is being shared, remains unclear. Much is hidden from us too: information is withheld, details edited out or enhanced. These are fragments of anecdotes, names of relatives whom we don’t know.

Ed Atkins

The worm 2021

Video stills

© Ed Atkins. Courtesy the artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

What the ‘worm’ of the title is remains a mystery. It could be the avatar, if we treat Atkins’s double like a character in a work of fiction, rather than a sincere representation of the artist. A character who indicates with his deep and meaningful looks that he’s engaged in a complex process of self-examination but might be exploiting the set-up for creative gain. The ‘worm’ might alternatively allude to emotional inheritance, passed from generation to generation. Or it could describe the insidious technology system that encourages oversharing of the deepest part of a person’s heart, only for the result to land in a soulless media space with no defined boundaries. It brings to my mind William Blake’s poem ‘The Sick Rose’, updated for the 21st century: the flower infected by an ‘invisible worm, / That flies in the night’, which has ‘found out thy bed / Of crimson joy: / And his dark secret love / Does thy life destroy.’

Recently, Atkins has replaced his digital doubles with flesh-and-blood actors. The play Sorcerer 2022, written with poet Steven Zultanski, is set in an ordinary-looking apartment where a group of friends meet to hang out. They don’t talk about much, but a strange atmosphere builds. The tone is not quite realism, not quite absurdism either. One of the characters mimes removing her eyes. When the friend who owns the apartment is alone, he too mimes removing his eyes, also peeling off lips, unbolting a molar, and unzipping his scalp. It is as if he’s getting undressed, putting these features in a drawer until he must put them on again the next day. Something would be lost if Atkins had one of his digital doubles take their eyes out and hang their skin suit in a wardrobe. Mime makes the act look like a private ritual: this character can’t remove his real body parts, but some deep sense of anguish drives him to symbolise doing so each night before bed. Allusion is powerful, and what is left to the imagination is more disquieting than literal depiction.

In Nurses Come and Go, But None for Me 2025, actor Toby Jones reads an account of terminal illness to a small audience. The artist’s father died of cancer in 2009 and he has said: ‘I’ve spent so many years making work as a more or less direct consequence of my father’s death.’ The Nurses… script is from a diary that Atkins’s father made after his diagnosis, with the blackly funny title Sick Notes. Later in the film, Jones is ‘healed’ by the Ambulance Driver – Saskia Reeves – during a role-playing game that Atkins devised with his daughter, in which she plays a fairy princess, Stardust, who needs curing of Dragon Disease.

Ed Atkins

Children 2024–5

© Ed Atkins. Courtesy the artist and Cabinet Gallery, London

Atkins’ grief is clear in his art. Doubles that can’t speak, trapped in states of emotional crisis. Self-portraits that look like cadavers. Meticulous renderings of the human body, as if the self might be found in hair follicles or flakes of skin; as if a person can be brought to life if enough detail is put into their image. Or be resurrected by a symbolic game if the correct sequence of words and actions is found. A feeling of loss is far greater than any artwork can contain – it tumbles and torques the living, and may one day even settle but will never go away. Grief and love lie beyond language, which returns us to the role of detail and absence in the creation of character and narrative: a little information is helpful, but too much mandated meaning is suffocating, deadening. Room must be made for the unknown.

And room must also be made for the cycle of life. During COVID, Atkins began making drawings on Post-it notes in coloured pencil, which he’d put in his daughter’s lunchbox each day: A happy ghost. A worm asking: ‘Are you pooing?’ A nut, a giant foot, a landscape. ‘Everything I was meant to be working on had been cancelled or indefinitely postponed,’ he explains. ‘Often, the drawings were the only thing I made in a day.’ Atkins kept the drawings – ‘sometimes blotched and warped by a satsuma or softened by proximity to a banana’ – and he talks about them with pride. They’ve become devotional objects. ‘My capacity to draw, my imagination, the site of art-making as a place of learning love – these are things I got from my mother, my father and my brother. Processes like this are bonding and profound.’ All the pulsations of a person.

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain, 2 April – 25 August.

Dan Fox is a writer, filmmaker and musician based in New York.

Supported by The Ed Atkins Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Curated by Polly Staple, Director of Collection, British Art and Nathan Ladd, Curator, Contemporary British Art, with Hannah Marsh, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art.