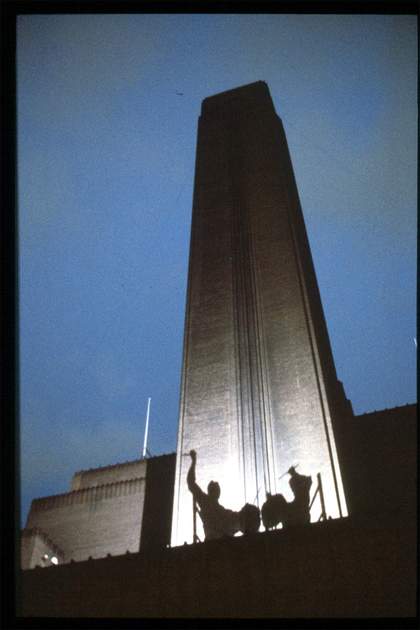

The finale to Anne Bean and Paul Burwell’s Lift Off, Bankside, 1993. ‘It was the biggest explosion I’d ever heard’, says percussionist Ansuman Biswas

LIFT/PH/1993/011/002/010 ‘Lift Launch photographs’ (1993). Image provided by Special Collections & Archives, Goldsmiths, University of London. Photo © Patricia Crummay

In spring 1993, performance artist Anne Bean and percussionist Paul Burwell knocked on the window of the office at Bankside Power Station. They had just been commissioned by London International Festiva l of Theatre (LIFT) to create a celebratory performance for its tenth anniversary. Of the submitted applications, theirs was the ‘least bonkers idea’, say Rose Fenton and Lucy Neal, co-founding directors of LIFT.

Bean remembers two caretakers at the site ‘bored out of their heads’, who casually agreed to let them use the former power station as a stage for their performance. Inside the building she found the machinery – including the giant turbines that later gave the Turbine Hall its name – still in place: ‘It felt like the dying days of a dynamic fiefdom.’ The site had been practically derelict since it ceased production of oil-fired energy in 1981, but it was, Bean says, ‘utterly magnificent’. ‘We realised immediately that it had immense possibilities.’

Ansuman Biswas, a percussionist and interdisciplinary artist who collaborated with Bean and Burwell on the performance, remembers Bankside as being ‘full of ghosts’. ‘It had that sense of beauty in dereliction. In something once powerful but now a decrepit shell of itself.

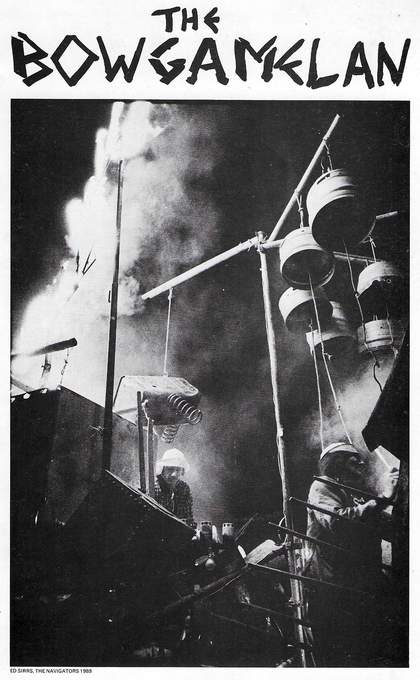

Another appealing trait was Bankside Power Station’s position beside the Thames. Bean, Burwell and Richard Wilson, a sculptor, knew the river intimately. They had first met at artists’ studios at Butler’s Wharf, on the South Bank near Tower Bridge. Burwell and Wilson both had boats, and ‘out of curiosity’, explains Bean, the three of them explored the Thames and its smaller tributaries. During a boat trip up Bow Creek in 1983, the trio formed what became known as Bow Gamelan Ensemble, and their work quickly became associated with the river. For their work The Navigators 1989, they spent six weeks living on a flotilla of barges on the Thames, presenting a series of waterborne performances.

Percussionist Z’ev performs in Bow Gamelan Ensemble’s Offshore Rig 1987 staged around Lot’s Ait island, River Thames

Courtesy Anne Bean

Ten years earlier, Bean staged an event with Burwell’s rowing boat. ‘We had drum kits on the boat, and I swam in the Thames right under Tower Bridge’, says Bean. The piece used dramatic lighting and sound effects, and played with echo and shadow. Eventually the Thames River Police came, sirens blaring, and shone their searchlight on Bean, casting an enormous shadow: ‘It was as if we’d arranged it’, she says. ‘We suddenly realised we could take on the city.’

When Bankside Power Station presented itself as the site for their next performance, Burwell and Bean decided to create an urban, primal incantation to London. They invited Biswas to compose a score for a group of 25 drummers. ‘It started with an instrument Paul had invented, which he called a daisy drum, which was also a sort of sculptural object’, Biswas explains. Burwell made them from oil drums, welding on drum hoops fitted with 22-inch Evans skins. ‘They were cheap and you could beat the hell out of them’, Biswas says. On the other end of the drum, they fitted a ring of paper rope soaked in paraffin, to be lit during the performance. ‘When you hit the drum, a column of air would move through and throw out this huge flame. My job was to coordinate a group of drummers who were basically playing flamethrowers.’

Poster for Bow Gamelan Ensemble’s The Navigators, part of LIFT 198

Courtesy Anne Bean

On Sunday 13 June 1993, hundreds of guests travelled to a then obscure part of London. Richard Gray, who now works in °Õ²¹³Ù±ð’s HR department, was there and recalls Bankside Power Station as ‘this slightly sinister building that I’d never heard of before. It felt like some hidden corner of London.’

The 25 drummers were divided into four squadrons, placed high up across two levels of the building, bisected by the chimney. The daisy drums were fixed to the parapet, facing outwards so that the flames would shoot towards the river.

The performance started with patterns of drumming, radiating ‘left to right, backwards, forwards, upwards, downwards’, says Bean. It was ‘an extremely physically strenuous thing’, says Biswas. He remembers being ‘drenched in sweat’ with ‘bleeding hands’. ‘It was like being in a battle.’

Alongside the fire drumming, a strobing flare cast a sharp shadow of Burwell and fellow drummer Steve Noble onto the chimney, while Catherine wheels were ignited from remote-controlled model helicopters. At one point, Burwell set off a long string of Chinese firecrackers and Biswas recalls that the sound literally flung him through the air: he would have been thrown off the parapet if Burwell hadn’t caught him. ‘That was the muscular power of the sound we were creating.’

Meanwhile, the helicopters lifted flaming paper ropes up into the sky, making a symmetrical curtain that framed the chimney. One of the helicopters dropped a rope – ‘a huge flaming python falling out of the sky’.

During Lift Off 1993, drummers Paul Burwell and Steve Noble were lit up with a strobing flare, casting a shadow onto the chimney of Bankside Power Station

Courtesy Anne Bean

For the finale, a paraffin explosion was rigged inside the chimney. A 30-foot column of flame shot from it, like a colossal Roman candle. ‘It was the biggest explosion I’d ever heard’, says Biswas. ‘We woke it up’, adds Neal. Then there was silence, and slowly, in the far distance, the sound of sirens as the emergency services from all over London began to converge on Bankside. ‘We always called [the sirens] our coda’, says Bean. ‘Paul’s attitude was to ask for forgiveness, not permission’, remembers Biswas. Fenton and Neal recall ‘a party of serious-looking Chief Fire Officers’. ‘We told them that we were theatre artists; it wasn’t as bad as it looked.’ The organisers had, in fact, informed the police, warned local residents and invited the mayor.

The following morning, Dennis Stevenson, chair of Tate Gallery, called Fenton and Neal and asked for a photograph of the event. The gallery was looking for new premises for its ambitious new museum of international contemporary and modern art. In April 1994, Bankside was announced as home to the new ºÚÁÏÉç.

Today, Bean looks out over the wide, grey expanse of ºÚÁÏÉç’s Turbine Hall. ‘Paul and I had the catalytic sense that all that has happened, and will happen here is a continuation of our performance.’

TATE MODERN

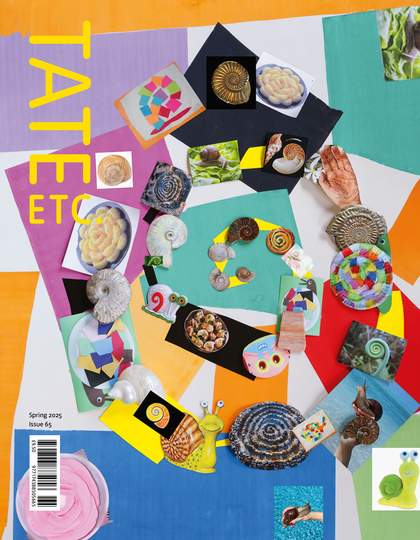

Look out for a feature celebrating 25 years of ºÚÁÏÉç in Tate Etc. issue 65, spring 2025.

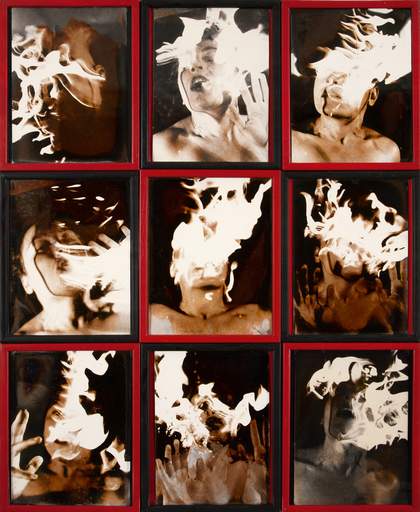

Anne Bean’s Heat 1974–7 was purchased with funds provided by Tate Patrons in 2024.

Figgy Guyver did work experience at LIFT in 2010 and is now Assistant Editor of Tate Etc.