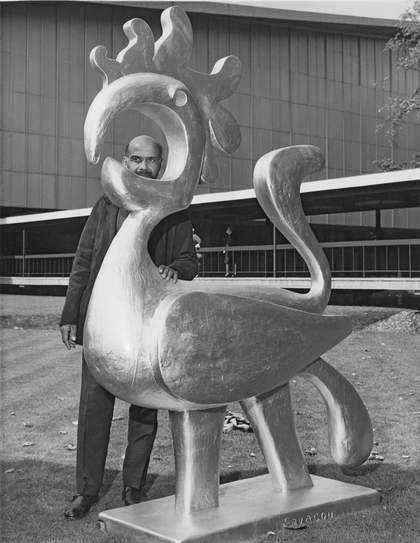

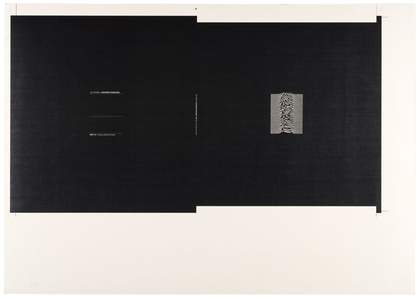

Peter Saville

Joy Division ‘Unknown Pleasures’ proof 2000

© Peter Saville and Joy Division. Image sourced by Bernard Sumner from the Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Astronomy (2nd edition, 1978). Photo © Tate

There are places, just as there are people and objects and works of art, whose relationship of parts creates a mystery, an enchantment, which cannot be analysed.

Paul Nash, Outline: An Autobiography and Other Writings (1949)

I recently had an uncanny experience in the Tate Archive. There I was, sitting with a printer’s proof of the artwork for Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures (1979), an album that was so important to my visual and musical education. The image depicts the radio waves emitted by a collapsing star, but I also can’t help seeing hills and mountains. It is the visualisation of something invisible: the topography of sound, an aural landscape. The image has been reproduced so many times, in so many different places – I remember my mother even had the iconic white-on-black graphic printed on a mug. My first thought, as I looked at it, was to text my siblings the news that I was holding this vision in my hand.

My sister is six and a half years older than me and was a teenager at the tail end of the acid house era. When I was growing up in the 1990s, she was my gateway into music. Sneaking into her room, I would be mesmerised by arcane, anonymous tapes and white-label dance records. Alongside these were the Factory Records releases with artwork designed by Peter Saville. Albums by groups like New Order, Section 25 and A Certain Ratio were part of the peripheral culture of raving. This is the music we would play in the car on the way to a party or the next morning, feeling bleary-eyed and slightly worse for wear.

The work I have been making for the past few years has explored points of convergence between rave culture and modern British landscape painting. In particular, I have been thinking about the acid house movement alongside the work of artists such as Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland and Edward Burra, whose paintings I first saw when I was taken to Tate Britain as a child. To me, there is a tradition – and a streak of activism – connecting the visionary landscapes of these painters to the transcendental nature of losing oneself in a field with friends.

Nash was deeply interested in the idea of genius loci or spirit of place. His landscapes divulge the hidden, spiritual aspects of nature. For him, there are places all over England where, for no definable reason, something magical happens – a sort of portal opens that transports you to another plane. Similarly, the repetitive beats associated with dance music have often been linked to a type of spirituality, offering a path to a higher state of consciousness.

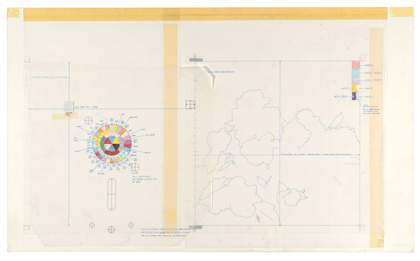

I am considering this connection when I turn to one of the original drawings for New Order’s 1983 album Power, Corruption & Lies, in which I see a disc shape, segmented into many differently coloured sections, each with a line radiating from it and labelled with a four-colour ink code. I recognise these as instructions to the printer for implementing Saville’s ‘colour alphabet’, a graphic system he devised, by which colours could stand in for letters and numbers, allowing him to remove all text from his record sleeve artworks.

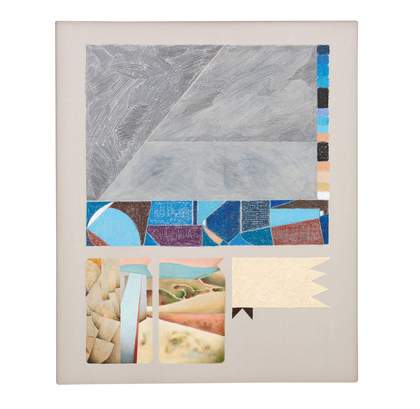

Today, the graphic also reminds me of an Indian tantric painting or perhaps a Sufi diagram visualising the soul’s journey from the earthly realm to the astral: a map of the ineffable, the invisible made visible. Maybe I’m drawn to this idea as I have mild synaesthesia. When I make one of my three-part works – painting/carving/sculpture – I start by listening to a piece of music and materialise the moving forms that appear in my mind by scratching them out on stained layers of gesso applied to a wooden panel. I do this over the course of a few frenzied hours before the material completely dries; the rhythm and the energy of the music is embedded in this top section of the work. Then, in the bottom left of the panel, I’ll paint a fragment of a British landscape work that suggests itself to me and which feels clean in the composition. In the bottom right, using oil stick in a particular way to resemble embroidered thread, I’ll reproduce a section of an Indo-Persian textile pattern – these, too, often being visual representations of the infinite, symbolise a journey of transcendence from the material to the spiritual.

Before I leave the archive, I remember another painting from my childhood visits to °Õ²¹³Ù±ð’s collection: Graham Sutherland’s Entrance to a Lane 1939. This semi-abstract swirl of a landscape depicts a wooded country path, promising a view that is just beyond our grasp. Paintings like this, while they can appear run-of-the-mill English at first glance, remind us that the landscape can be such a mystical and magical thing. A portal to experiences yet to be discovered or encountered. Unknown places leading to unknown pleasures.

Peter Saville’s lithographic prints, production proofs and original drawings produced for records issued by Factory Records were presented by Peter Saville and New Order in 2023. Find out more about the archive collections, and how to arrange your own visit, at tate.org.uk/art/archive. Paul Nash’s Equivalents for the Megaliths was purchased in 1970 and is on display at Tate Britain.

Haroun Hayward is an artist based in London.