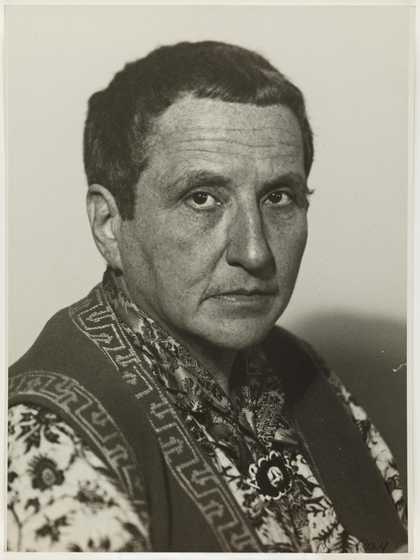

Man Ray

Gertrude Stein (│”.1920ŌĆō9)

Tate

Image meant everything to Gertrude Stein. She dated her emergence as a groundbreaking writer to the rhythmic sentences she composed in her head while sitting for Picasso in 1905. After that famous portrait was finished (she would receive her visitors from a chair placed directly beneath it), Stein regularly harnessed the power of images to present herself to the wider world as she wished to be seen. While her avant-garde texts were widely derided by critics, Stein turned herself into a legend by canny self-projection, ensuring her name, and face, remained in the public eye, even when bemused publishers rejected her work.

She posed for more portraits, by Fe╠ülix Vallotton and Francis Picabia, was sculpted by Jacques Lipchitz and Jo Davidson, and captured by photographers from Carl Van Vechten to George Platt Lynes and Imogen Cunningham. If SteinŌĆÖs work was in danger of languishing unread, her image ŌĆō she determined ŌĆō would be rendered permanent. Across her portraits, Stein exudes authority: her cropped hair, her steadfast gaze, her flamboyant dress (patterned waistcoats, brooch glinting at the throat) declare her as someone who knows exactly who she is.

In her memoir, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), Gertrude Stein ŌĆō writing in the voice of her partner, Toklas ŌĆō describes her first encounter with Man Ray in 1921. Having been introduced to him at a party, ŌĆśToklasŌĆÖ writes about their visit to his Paris hotel:

It was one of the little, tiny hotels in the rue Delambre and Man Ray had one of the small rooms, but I have never seen any space, not even a shipŌĆÖs cabin, with so many things in it and the things so admirably disposed. He had a bed, he had three large cameras, he had several kinds of lighting, he had a window screen, and in a little closet he did all his developing. He showed us pictures of Marcel Duchamp and a lot of other people and he asked if he might come and take photographs of the studio and of Gertrude Stein. He did and he also took some of me and we were very pleased with the result.

Over the course of the 1920s, Man Ray was SteinŌĆÖs friend, agent and official photographer. His portraits of Stein were the first to be printed: the legend they created together propelled her home to the status of a tourist destination for Americans in Paris, eager to catch a glimpse of SteinŌĆÖs famous art collection and its eccentric, intriguing custodian. Man Ray regularly visited her apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus for photography sessions, capturing Stein sitting next to her Picasso portrait, writing at her desk or posing by the fireplace with Toklas. In addition, he zealously pitched features on her writing to magazines, from Vanity Fair to Vogue, to be accompanied by his photographs: ŌĆśYou see,ŌĆÖ he told her, ŌĆśI am doing my share to keep the pot boiling.ŌĆÖ

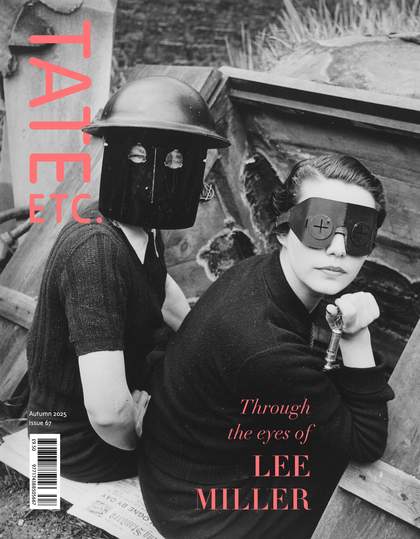

Man RayŌĆÖs photograph of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in the studio of their Paris home, 1922, also used on the cover of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933)

┬® 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust / DACS, London

Their correspondence ended abruptly in February 1930, when he asked Stein to send a cheque for 500 francs for his portraits of her, Toklas and their pet poodle, Basket. SteinŌĆÖs tart reply pointed out that she had never asked for a share of proceeds when he had sold his prints of her, clearly implying that the arrangement had been mutually beneficial. Three years later, he asked to include a photograph of her in a new book showcasing his portraits of writers, artists and musicians: ŌĆśYou are,ŌĆÖ he wrote, ŌĆśan important part of my development.ŌĆÖ In The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, the prominence Stein confers on her sittings with him suggests that she, too, considered the association formative: the photographs Man Ray took of her, she wrote proudly, ŌĆśare extraordinarily interesting.ŌĆÖ

Man RayŌĆÖs images of Stein are intimate and subtly performative: much like her own artful autobiography, they play wry games with genre and gender. One anecdote in the Autobiography is especially telling. Man Ray, writes Stein as Toklas,

has at intervals taken pictures of Gertrude Stein and she is always fascinated with his way of using lights. She always comes home very pleased. One day she told him that she liked his photographs of her better than any that had ever been taken except one snap shot I had taken of her recently. This seemed to bother Man Ray. In a little while he asked her to come and pose and she did. He said, move all you like, your eyes, your head,it is to be a pose but it is to have in it all the qualities of a snap shot.

Suddenly, the professional photographer, with all his expertise and studio paraphernalia, is trying to emulate a casual domestic photo ŌĆō not a photograph, but a ŌĆśsnap shotŌĆÖ ŌĆō taken by an amateur photographer (Toklas), who is able, despite her lack of training, to see her subject as no one else can.

Such overturnings of norms and hierarchies abound in the Autobiography, an audacious queer experiment disguised as a chatty memoir. Alice B. Toklas, our purported narrator and protagonist, fades into the background: the story she tells is entirely about the witticisms, achievements and glittering social life of Gertrude Stein. Yet in writing ToklasŌĆÖs ŌĆśautobiographyŌĆÖ on her partnerŌĆÖs behalf, Stein set out to show how everything she does is contingent on ToklasŌĆÖs approving gaze. Throughout the book, itŌĆÖs Toklas who brings Stein into being ŌĆō identifying her genius at their very first meeting, telling her life story, even capturing her likeness so deftly that the great Man Ray will seek to approximate her style.

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is full of fakes, doubles, layers and blurrings: itŌĆÖs no coincidence that its original cover image was a photograph taken by Man Ray, perhaps the only person who ever attempted to see Stein just as Toklas saw her. Stein is working at her desk, in shadow; the focal point of the image is Toklas, standing in the doorway. ItŌĆÖs a knowing wink at the bookŌĆÖs true authorship, and a witty rejoinder to the constraints of gender roles which Stein and Toklas ŌĆō in life, on the page, and in photographs ŌĆō set out to upend.

Gertrude Stein was accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax from the Estate of Barbara Lloyd and allocated to Tate in 2009. It is included in Monsieur Venus, a free display in Media Networks at ║┌┴Ž╔ń.

Francesca WadeŌĆÖs latest book is Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife, published by Faber.