Emily Kam Kngwarray

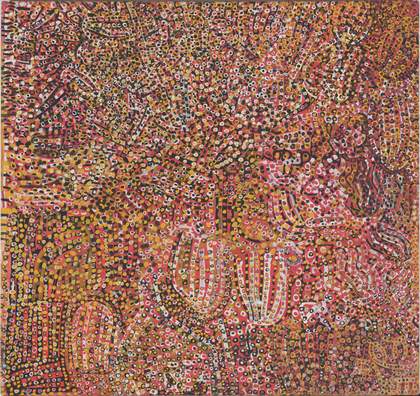

Untitled (Alhalker) (1989)

Tate

© Estate of Emily Kam Kngwarray / DACS 2025, All rights reserved

Find out more about our exhibition at ºÚÁÏÉç

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Untitled (Alhalker) (1989)

Tate

© Estate of Emily Kam Kngwarray / DACS 2025, All rights reserved

Tate respectfully acknowledges Australian First Nation Peoples. We recognise their continuing connections to Country and culture and we pay our respect to their Elders, past and present. We respectfully acknowledge all Traditional Custodians throughout Australia whose art we care for and to whose lands ºÚÁÏÉç exhibitions and staff travel.

Over half a century ago, Aboriginal artists from Central Australia began experimenting with new ways of expressing their ongoing cultural traditions. For millennia they had drawn on the ground, etched designs into rock and wood, and painted on the body for ceremonies. They then started to create art using watercolour and acrylic paint, and techniques such as batik. Emily Kam Kngwarray (c.1914–1996) was at the forefront of this artistic revolution. Her unique style and powerful creative vision gained international attention, redefining the scope of contemporary art across the world.

Kngwarray was born in Alhalker, located in the Sandover region of the Northern Territory, Australia. Alhalker is Kngwarray’s Ancestral Country. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, the concept of Country encompasses the lands, skies and waters to which they are deeply connected, over countless generations. Country is a shared place of spiritual, social and geographical origins. Kngwarray’s art embodies her detailed knowledge of the places she lived in throughout her life. She layered motifs representing the plants, animals and geological features that formed the desert ecosystems around her.

This exhibition follows the development of Kngwarray’s artistic career, beginning with some of her early batik works. It was developed in close collaboration with the Utopia Art Centre, Northern Territory, and the National Gallery of Australia. Kngwarray’s descendants have been deeply involved in the exhibition. Their knowledge of their Country and Kngwarray’s work is integral to everything you will see, hear and read.

Kngwarray spoke Anmatyerr – one of many Aboriginal languages from the desert regions of the Northern Territory. Anmatyerr shares many words and grammatical features with Alyawarr, a neighbouring language. In some communities, people speak both Alyawarr and Anmatyerr.

In Anmatyerr society, everyone has one of eight skin names in addition to other personal names. Skin names are an important part of the kinship system. They reflect relationships between people, as well as between people and their Country and Dreamings. A person has the same skin name as their siblings and some of their grandparents. A person has a different skin name to their children and their parents. Emily Kam’s skin name was Kngwarray.

With the support of Kngwarray’s family and community, Tate has adopted the spellings of Anmatyerr words used in the Central and Eastern Anmatyerr to English Dictionary, which was published in 2010. Tate has also applied this spelling system to the titles of artworks in the exhibition.

In the exhibition texts, where possible, we use Aboriginal place names alongside English ones. We also include the Anmatyerr terms for plants, animals and concepts important to Kngwarray. Kngwarray did not always provide titles for her art works. However, some titles, especially those with Anmatyerr names, do give an indication of her subject matter.

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Ntang Dreaming 1989 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025

In the early 20th century, when Kngwarray was a young girl, Alhalker Country still lay beyond areas of inland Australia that were managed by white settlers. However, Kngwarray and her countrymen and women were not immune to the on-going and devastating effects of colonisation. The settlers changed Ancestral Aboriginal lands by introducing sheep and cattle, building fences, and sinking bores to access water. Around this time, Kngwarray saw white people for the first time. She remembered this frightening encounter – she thought the newcomers were arrenty (devils, monsters).

During this period, an area to the east of Alhalker Country was taken over by settlers and renamed Utopia. Many Aboriginal people, including Kngwarray, worked on these newly formed pastoral properties, usually in exchange for rations rather than wages. Kngwarray kept watch over livestock and worked in kitchens.

Kngwarray’s art is grounded in her understanding of her Country and of the Dreamings originating there. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, the concept of the Dreaming or Creation time is fundamental to their social, cultural and spiritual practices. Ancestral beings, popularly known as Dreamings, manifest themselves in Country and its many diverse life forms. Plants, animals and natural phenomena, such as wind, fire and rain, travel across Country, shaping landscapes as they go. Important places and their Dreamings are celebrated in songs and ceremonies. Of special significance to Kngwarray are ankerr (emus) and anwerlarr (pencil yams). She was named after kam, the seeds and seedpods of the pencil yam.

In this room are artworks Kngwarray made between 1980 and 1991. Several of her early batiks and paintings feature ankerr (emus). In Anmatyerr culture, these large, flightless birds are highly respected. A rich and extensive lexicon of terms exclusively applies to them. For example, there are specific words for young and old emus. There are also particular terms for parts of their bodies – their necks, feet and feathers – that do not apply to any other bird or animal.

The prominence Kngwarray gave to emus highlights their importance as a Dreaming for Alhalker Country. Emus are one of the main themes in the women’s awely ceremonies from there. Kngwarray’s work also references their different behaviours. Old Man Emu with Babies reflects the fact that it is the male emu who cares for the emu chicks. Their three-toed footprints spread across the canvases and batiks, showing their paths as they travel between water sources in Alhalker Country.

In 1987, an Aboriginal-controlled organisation called Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) began to coordinate the Utopia Women’s Batik Group. CAAMA commissioned artwork by artists from several communities, helping to sell work, and organising exhibitions and publications. It was in this context that Kngwarray started to attract increasing public attention.

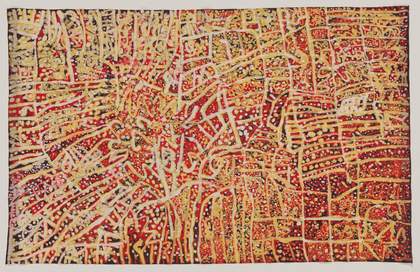

Emily Kam Kngwarray, not titled, 1981

National Gallery of Australia. © Estate of Emily Kam Kngwarray / DACS 2024, All rights reserved

The freestanding works in the centre of the room are batiks that Kngwarray made between 1980 and 1988.

Batik is a form of textile art, originally from Indonesia. Artists draw their designs on the fabric with hot wax, using a brush or a small spouted tool called a canting. They can also use a wooden or metal stamp called a cap to make imprints with the wax. A batik artist must work quickly, before the wax cools. When the fabric is immersed in dye, the wax resists the dye, so only the parts without wax take up the colour. After the fabric is dry, the cloth can be waxed and dyed again to create elaborate, multicoloured designs. The beauty of the batik is fully revealed after the wax is removed.

Women working in the Sandover region made batik outdoors, heating the wax in metal pans over open fires. They sat on the ground when applying the wax and stretched the fabric over their laps or on cardboard cartons. Flour drums of water were used to boil the wax out of the cloth.

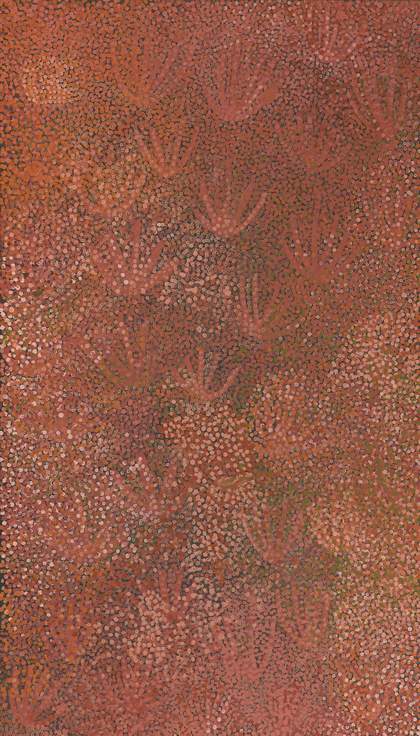

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anwerlarr (pencil yam) 1990

National Gallery of Australia. © Estate of Emily Kam Kngwarray / DACS 2024, All rights reserved

Anwerlarr (pencil yam) is an important Dreaming from Alhalker Country. The plant has yellow flowers, bright green trifoliate leaves, and long trailing vines that can form a tangled mat on the ground or twine around other nearby vegetation. Pencil yams belong to the legume family of plants. People usually dig up their edible roots after the surface vine dies off. These are cooked lightly in hot earth and coals or eaten raw.

In the next two rooms, you will find stippled and dotted paintings Kngwarray made between 1990 and 1992. They are larger than her earlier works, scaled to encompass the breadth of her subject matter. Across these works, Kngwarray paints distinctive motifs, including pencil yam tubers and emu tracks. These images are almost completely submerged by fields of dots that expand or contract across the surface of the canvas to create an impressionistic representation of Alhalker, her Country.

The pencil yam grows in our Country – it belongs to us – the anwerlarr yam. They are found growing up along the creek banks. That’s what I painted.

Emily Kam Kngwarray, 1992

In early 2023, a women’s camp was held in Alhalker and Anangker Countries as part of the community consultations for this exhibition. It was a highlight – an occasion for remembrance, reunion and celebration. The women searched for anwerlarr yams (pencil yams), which were prolific after summer rains. They shared their knowledge of other plants and animals that inspired Kngwarray’s artworks. They performed the awely ceremonies for Alhalker and Anangker. This film captures some key moments in that event.

The ecosystem of Alhalker Country is typical of the arid zone of central Australia. It includes low-lying ridges, rocky outcrops, woodlands and undulating sandplains, some permanent waterholes and winding ephemeral watercourses. Alhalker is home to the many plants and animals that inspired Kngwarray’s artworks.

AlhaIker is the place where Kngwarray was born, and where she lived during her younger years. The name refers to a particular place, but also to a broader geographic area for which certain Anmatyerr people have custodial rights and responsibilities. This thread of inheritance has continued through countless generations.

Alhalker Country is closely related to Anangker Country to the north-west. The two places are regarded as siblings by Anmatyerr people. Anangker is the elder one. Some Dreamings and songs are shared between these Countries. The family groups connected to these places are close kin, with many similar life experiences. Women from Alhalker and Anangker worked together in the preparation of this exhibition.

In 1993, Kngwarray started painting bold lines on canvas and paper, beginning a new and prolific period of image-making. Some were black and white, while others included her familiar palette of reds and yellows, along with bright bursts of colour. The power of these works comes from the energy of her repeated lines and brushstrokes. Some people have interpreted these paintings as representing designs painted on the body for awely (women’s ceremonies).

The paintings in this room have a rhythmic quality, evoking the beat of ceremonial songs and the dance movements that are carefully choreographed representations of the Dreaming. The meanings of the awely songs are multilayered, often using poetic words not found in everyday spoken language. In the Alhalker songs, one verse refers to an emu who is travelling along and bending down to eat fan-flower and desert raisin fruits. As the women dance, they embody the actions of this Ancestral emu.

Kngwarray learnt awely from her mother. ‘We all used to dance at Alhalker, all the Alhalker women. We danced, following the Dreaming’, she said.

Works in this room were included in the 1997 Venice Biennale, an international art exhibition. Kngwarray was one of three Aboriginal artists selected to represent Australia that year.

Anwerlarr (pencil yam) is an important Dreaming for Alhalker, Kngwarray’s Country. The plants flower and then seed underground as well as above the ground. Their seedpods and encased seeds are called kam – Emily Kam Kngwarray’s namesake. Kam change colour – they are white, then yellow, and then reddish brown as they age. The transformations of colour are likened to the life stages of people – the white ones are ampa akely (children), the yellow ones awenk (teenage girls) and the reddish-brown ones are arelh ampwa (old women).

I paint my plant, the one I am named after – those seeds I am named after. Kam is its name. Kam. I am named after the anwerlarr plant. I am Kam!

Emily Kam Kngwarray, 1992