Salvador Dal├Ł

Lobster Telephone (1938)

Tate

┬® Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2025

1. SURREALISM BEYOND BORDERS

A telephone receiver morphs into a lobster.

A train rushes from a fireplace.

These are images commonly associated with Surrealism, a revolutionary cultural movement that prioritised the unconscious and dreams, over the familiar and everyday. Sparked in Paris around 1924, Surrealism has inspired and united artists ever since. This exhibition traces its wide, interconnected impact for the first time. It moves away from a Paris-centred viewpoint to shed light on SurrealismŌĆÖs significance around the world from the 1920s to the 1970s. It includes artists who embraced this spirit of revolt and those who shared Surrealist ideas and values but never joined a group. It features some who have intersected with Surrealism at various points ŌĆö working in parallel, associated loosely or for a short period, or counted in by other Surrealists.

Surrealism is an expansive, shifting term, but at its core, it is an interrogation of political and social systems, conventions and dominant ideologies. Inherently dynamic, it has travelled and evolved from place to place and time to time ŌĆö and continues to do so today. Its scope has always been transnational, spreading beyond national borders and defying nationalist definitions, while also addressing specific and local contexts. In a world defined by territorial control ŌĆö and the consequential ideological constraint, expansionist conflict, and exploitative colonialism ŌĆö Surrealism has demanded liberation and served artists as a tool in the struggle for political, social and personal freedoms. The exhibition reflects this individualism by avoiding nationalities. Instead, it highlights the centres where Surrealists worked and gathered, recognising shared practices and ideals even as territories and place names changed around them.

The artworks assembled here reveal some, but certainly not all, of the many routes into and through Surrealism. Artworks are grouped in broad areas of Surrealist activity, presenting collective interests and networks shared by artists across regions at points of convergence, relay and exchange. They also demonstrate individual challenges witnessed in the pursuit of independence from colonialism, as well as the experience of exile and displacement caused by international conflict. Combining broad themes and detailed points of focus across its sections, the exhibition is neither singular in narrative nor linear in chronology. Instead, it challenges conventional accounts that centre Surrealism in Europe, presenting an interrelated network of activity ŌĆö one that makes visible many lives, locations, and encounters linked through the freedom and possibility offered by Surrealism.

2. POETIC OBJECTS

Making Surrealist objects can be a powerful way to subvert the everyday. As well as challenging the traditional look of sculpture, the works shown here reinvest everyday objects with what Parisian poet Andr├® Breton, author of the 1924 Manifeste du surr├®alisme (Manifesto of Surrealism), called a ŌĆśderangement of the senses.ŌĆÖ Often made with unconventional, found or discarded materials such as bones, shells or leather scraps, these assemblages produced by artists connected to Surrealism, draw their impact from the imaginative spark lit by the joining of otherwise unrelated elements. For some, this was typified by a phrase from the 19th-century Montevideo poet Isidore Ducasse (the self-styled Comte de Lautr├®amont), ŌĆśas beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating tableŌĆÖ.

Wolfgang Paalen described Surrealist objects as ŌĆśtime-bombs of the conscience,ŌĆÖ while Salvador Dal├Ł called them ŌĆśabsolutely useless from a practical and rational point of view and created wholly for the purpose of materialising in a fetishistic way, with maximum tangible reality, ideas and fantasies of a delirious character.ŌĆÖ In their materials and manufacture, objects such as those shown here by Eileen Agar and Joyce Mansour could produce unexpected responses. At their most powerful, poetic objects escape any single interpretation.

THE UNCANNY IN THE EVERYDAY

ŌĆśThe only thing that fanatically attracts me,ŌĆÖ wrote Jind┼Öich ┼Ātyrsk├Į in Prague in 1935, ŌĆśis searching for surreality hidden in everyday objects.ŌĆÖ This reflects SurrealismŌĆÖs relationship with the ŌĆśuncannyŌĆÖ ŌĆö a familiar sight made disconcerting and strange by the unexpected.

Alerted by psychiatrist Sigmund FreudŌĆÖs writing on the uncanny, Surrealist artists have tapped into the rich vein of strangeness embedded in the ordinary world. Photography proved particularly well suited to the project of recording these accidental coincidences, repetitions, and hazards of daily life. Manuel Alvarez Bravo and Dora Maar captured surprising objects and scenes encountered through chance. Others, including Raoul Ubac and Limb Eung-sik, manipulated

or staged images to convey a sense of the uncanny.

With its potential to reveal hidden truths, the uncanny is well suited to satire and political subversion. To this end, photographic strategies of ŌĆśdefamiliarisationŌĆÖ have been employed to subvert reality and present everyday scenes in strange or uncanny ways. This is seen in works shown here by artists working in Belgrade, Bucharest, Lisbon, Mexico City, Nagoya, Prague and Seoul, guaranteeing an ongoing questioning of power and society, even in the face of dire threats.

3. THE WORK OF DREAMS

Leonora Carrington Self Portrait ca. 1937ŌĆō38 Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, USA) ┬® The estate of the artist, DACS, 2021

Surrealism has questioned ŌĆö and sometimes attempted to overthrow ŌĆö the strongholds of consciousness and control. Dreams are critical to this end because, like hallucinations and delusions, many have believed that they can reveal the workings of the unconscious mind. In some works on show here, fantastical juxtapositions or nightmarish subjects capture the sense of the ordinary made unfamiliar. Surrealist artists in various locations have seized this potential for liberation. They seek the inspiration of dreams to break from limitations imposed by societal customs, or to bring the self, community, or work of art beyond the reach of waking reality.

Sigmund FreudŌĆÖs widely translated book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) provided an early, vital stimulus for many artistsŌĆÖ approaches to Surrealism. Through case studies of his patients, Freud believed that dreamsexposed emotions otherwise repressed by social convention. Max ErnstŌĆÖs painting, for example, draws upon such an experience: a ŌĆśfever visionŌĆÖ in which he saw forms appear in the graining of wood panelling.

REVOLUTION, FIRST AND ALWAYS

Revolution is a central idea for Surrealism, as it offers the possibility for transformation and liberation. Since its conception, Surrealism has challenged predominant systems of power and privilege, division and exclusion, and has been emboldened by a growing chorus of voices. Alongside the cultural and sociopolitical forces that determined its own evolving history over the last century, Surrealism has presented a model for political engagement and agitation for artists, many of whom have been arrested for ŌĆśsubversiveŌĆÖ behaviour.

While Surrealists have expressed revolutionary ideas in poetic and artistic terms, some, including those assembled here, have also generated collective actions. They have condemned imperialism, racism, authoritarianism, fascism, capitalism, greed, militarism, and other forms of power and control. From student, civil rights and antiwar protests, to the decolonisation movement, Surrealism has served as a tool, but not a formula. As L├®opold Senghor, Surrealist poet, first president of Senegal and cofounder of the Black consciousness movement ▒Ę├®▓Ą░∙Š▒│┘│▄╗Õ▒ explained in 1960: ŌĆśWe accepted Surrealism as a means, but not as an end, as an ally, and not as a masterŌĆÖ.

4. CONVERGENCE POINT: THE BUREAU DE RECHERCHES SURR├ēALISTES, PARIS

On 11 October 1924, the Paris Surrealists opened the Bureau de recherches surr├®alistes (Bureau of Surrealist Research). The poet Antonin Artaud, who functioned as its director, called it an ŌĆśagency of communicationŌĆÖ. Established as a gathering place, the Bureau aimed to ŌĆśreclassify lifeŌĆÖ. Members assembled an archive of materials relating to the Surrealist revolution. They collected dream narratives, documented trouvailles (finds) and chance occurrences, and prepared projects such as a ŌĆśglossary of the marvellousŌĆÖ. It was decorated to surprise visitors ŌĆö with a plaster cast of a womanŌĆÖs body hanging from the ceiling and Giorgio de ChiricoŌĆÖs Le R├¬ve de Tobie (The Dream of Tobias) on a wall.

The Bureau served a range of public functions. These included receiving visitors, circulating collective pamphlets and group publications, or papillons (ŌĆśbutterfliesŌĆÖ), responding to press enquiries and issuing the groupŌĆÖs first journal, La R├®volution surr├®aliste. In this way, it was a point of convergence as much as a crossroads for circulation. Newcomers interested in Surrealism visited to learn about, contribute to, and even join the movement. Members fielded questions, stimulated by their exchange of ideas and talent for publicity. Subscribers from all points ŌĆö whether Adelaide, Bucharest, Prague or Rio de Janeiro ŌĆö made contact and shared their own news of Surrealist activities

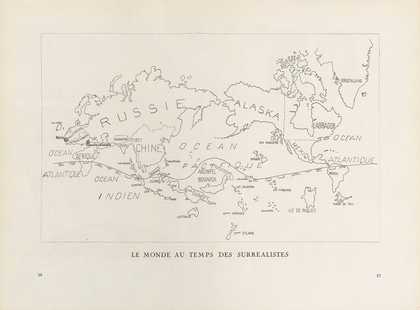

5. THE WORLD IN THE TIME OF THE SURREALISTS

The drawing captioned Le Monde au temps des surr├®alistes (The World in the Time of the Surrealists), published in 1929 (and enlarged for our exhibition entrance), reimagines the world. Challenging geopolitical conventions that use maps as a tool to define territories, the SurrealistsŌĆÖ growing anti-imperialist sentiments are demonstrated by placing the Pacific islands at the centre. They also give prominence to (Soviet) Russia, and erase the colonising powers of Europe, Japan, and the United States.

While embracing anti-colonial politics, Surrealists in Europe mistakenly perceived an affinity with art made by Indigenous peoples of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. This fantasy of shared ideas and perspectives is visible in early Surrealist collections, journals, and exhibitions. Objects made by Indigenous peoples were included in the 1936 exhibition of ŌĆśSurrealist objectsŌĆÖ in Paris. These works, included for their perceived aesthetic value within a European context, were stripped of place, maker and their original meaning. This exposes how, even in valuing the art of Indigenous peoples and deploring the systems of colonialism, Surrealists remained entangled within a colonial attitude of cultural appropriation.

6. COLLECTIVE IDENTITIES

"Le monde au temps des surr├®alistesŌĆØ (The World in the Time of the Surrealists), from Vari├®t├®s (Brussels), special Surrealist number, June 1929 Tate Library

Surrealism depends upon a collective body of participants, often working together in response to political or social concerns. This unity acknowledges that working collaboratively is often more powerful than as an individual in isolation. Viewed across time and place, this quality has been manifested in group exhibitions and demonstrations, cowritten manifestos and declarations, and broadly shared and circulated artistic, political and social values.

Collaborative pursuits could release what Simone Breton, an early participant in Surrealism in Paris, called ŌĆśimages unimaginable by one mind alone.ŌĆÖ Examples of such generative activities include se├Īnce-like explorations of trances by Breton and her colleagues, questionnaires published in the Belgrade Surrealist CircleŌĆÖs journal, and the Chicago SurrealistsŌĆÖ spoken-word poetry performed with musicians. This collectivity has been expressed through art making, especially evident in the multiple cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) drawings gathered in this room. These are made by one participant drawing a form and, after folding the paper, passing it on so that only the ends can be seen by a second person who continues the work and passes it on again. Group production fosters proximity and intimacy, but it can also connect and make visible diasporic and transnational communities.

7. CONVERGENCE POINT: HAITI, MARTINIQUE, CUBA

Caribbean islands have been both places of convergence and relay for Surrealism. Many manifestations originated on the islands in multiple and concurrent waves. In Martinique, Surrealism took root in 1932, when a group of students, including writer and theorist Ren├® M├®nil, produced the single-issue journal L├®gitime d├®fense (Self-Defence) from Paris. It aligned with the Black self-affirmation movement of ▒Ę├®▓Ą░∙Š▒│┘│▄╗Õ▒, while also attacking French colonialism. M├®nil ŌĆö as well as poets Aim├® and Suzanne C├®saire ŌĆö carried Surrealism to Fort-de-France. Their journal, Tropiques, launched in April 1941 and over its four years of publication, promoted Surrealism as a critical tool to cast off colonial dependence and assert MartiniqueŌĆÖs own cultural identity.

Surrealism did not travel intact but flowed, fragmented and was transformed. The focus on freedom found channels through the writings of Cl├®ment Magloire Saint-Aude in Haiti, and of Juan Bre├Ī and Mary Low in Cuba. Some connected with travellers, including exiles escaping the war in Europe. These included Eugenio Granell, who settled in the Dominican Republic in 1939. Two years later, Aim├® and Suzanne C├®saire encountered Andr├® Breton and Wifredo Lam, who were held by the authorities in Martinique. Their friendship strengthened the link between Tropiques and Surrealist activities in Cuba, Mexico and the US.

EUGENIO GRANELL, TRAVELLER

As a Spanish Republican, Trotskyist and a Surrealist, Eugenio Granell went into political exile following the end of the Spanish Civil War (1936ŌĆō39) and the defeat of the Spanish Republic. In 1939 Granell escaped to the Dominican Republic. During his six years there, he worked as a symphony violinist, held his first exhibition, and with a group of poets, launched the Surrealist journal La poes├Ła sorprendida (Poetry Surprised) in 1943. Andr├® Breton and Wifredo Lam also visited the island, resulting in lifelong friendships.

Under the increasingly authoritarian regime, GranellŌĆÖs radical politics became untenable. Relocating to Guatemala in 1946, he connected with artists and intellectuals including the painter Carlos M├®rida and the poet Luis Cardoza y Arag├│n. Arguing with and, ultimately, threatened by Stalinists, Granell then fled to Puerto Rico, where he remained until 1957. There he spurred a new interest in Surrealism, particularly among the university students who formed the Mirador Azul (Blue Lookout) group. Granell remained an energetic proponent of Surrealism, seeing in it ŌĆśfreedom for art ŌĆö and as a consequence, freedom for mankindŌĆÖ.

8. TED JOANS, TRAVELLER

Poet, musician, and artist Ted JoansŌĆÖs identity was shaped by travel and dislocation. To travel was to discard what he saw as the constraints of nationality, language, and culture. He left the US twice in rejection of its systematic racism: once in the early 1960s, and again, about 30 years later, following the murder by police officers of Amadou Diallo, a young Black man in the Bronx.

Joans formally engaged with the Surrealists after a chance meeting with Andr├® Breton in Paris. His saying ŌĆśJazz is my religion, Surrealism is my point of viewŌĆÖ reflects the fluidity of his lifestyle as he moved through North and Central America, North and West Africa, and Europe.

While travel allowed freedom, it also provided community, as represented in Long Distance, a more than nine-metre long collaborative cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) drawing that the artist began in 1976. It would move with Joans, growing with each invited contribution. Produced over 30 years (two beyond JoansŌĆÖs own life), between 132 participants, Long Distance extends the Surrealist idea of collaborative authorship to the people connected through JoansŌĆÖs travels.

9. BEYOND REASON

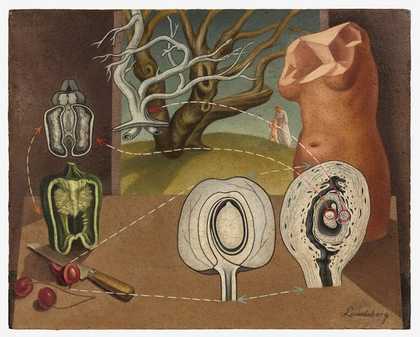

Helen Lundeberg Plant and Animal Analogies 1933ŌĆō34 The Buck Collection at the UCI Institute and Museum for California Art (California, US) ┬® The Feitelson/Lundeberg Art Foundation.

In Western Europe, modern political and intellectual thought was structured by the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement of the 17th and 18th centuries that promoted science, empirical knowledge and reason as the hallmarks of society. This attitude complemented the ideology of European imperial expansion and emphasised the importance of categorising and collecting knowledge. For Surrealists and their sympathisers, especially in Europe and North America, rejecting this oppressive rationalism meant liberating the mind from outdated modes of thought and behaviour. Surrealist artists have sought to challenge ŌĆśorderŌĆÖ by using visually precise techniques to create irrational images. This could be through extreme contrasts of form and scale, or by embedding apparently illustrative images in compositions that are anything but rational.

This aspect of Surrealism has been interpreted by artists in different ways. In Japan in the late 1920s and early 1930s, some artists ŌĆö confronted with economic and political pressures, and the criticism of Surrealism as merely escapist ŌĆö sought to distinguish their approach, identifying ŌĆśrishi (reason) as its only weaponŌĆÖ. In deflecting this politically-motivated attention, driven by the stateŌĆÖs shift to authoritarian militarism, they proposed ŌĆśan even higher form of Surrealism ŌĆö a new Surrealism which is Scientific SurrealismŌĆÖ. Various forms of Surrealism in Japan both celebrated and interrogated modern technologies, science, and reason in order to question the meaning of art, conventional ways of thinking, and cultural norms.

BODIES OF DESIRE

May my desires be fulfilled on the fertile soil

Of your body without shame.

These lines from Surrealist poet Joyce MansourŌĆÖs Cris (Cries, 1953) offer a counterbalance to traditional narratives about Surrealism, sexuality, and desire. The exploration of the unconscious has long presented Surrealist artists with a means to challenge forms of repression and exclusion dictated by prevailing social conventions. The most wellknown examples have been thoseŌĆösuch as Alberto GiacomettiŌĆÖs The Cage and Hans BellmerŌĆÖs manipulated photographs ŌĆö that reflect the complicated desires of heterosexual men and their gaze upon the female body.

The subject of desire is a recurrent theme in art associated with Surrealism and it has also encompassed more fluid identifications of gender and sexuality. For example, Lionel WendtŌĆÖs intimate studies of nudes explore the fluidity of desire, while Claude CahunŌĆÖs defiant performance of selfidentity also challenges fixed notions of gender. These images question traditional notions of privilege and power, while also acting as representations of the artistsŌĆÖ desires and fantasies.

10. CONVERGENCE POINT: CAIRO

In the months before the outbreak of the Second World War, with European nationalism on the rise, Surrealists in Cairo came together to form a vocal resistance. The group issued a manifesto in December 1938 written by Georges Henein with 37 signatories. ItsŌĆÖ title, Yahya al-fann al-munhatt / Vive lŌĆÖart d├®g├®n├®r├® (Long Live Degenerate Art), references the NazisŌĆÖs denunciation of modernist art as ŌĆśdegenerateŌĆÖ and in conflict with their fascist ideology.

The group of artists and writers known as al-Fann wa-lHurriyya / Art et Libert├® (Art and Liberty), used both the Arabic and French terms for ŌĆśfree artŌĆÖ as the framework for their Surrealist practice. Strongly critical of conservatism and the ongoing colonial British presence in Egypt, they aligned themselves with ŌĆśrevolutionary, independentŌĆÖ art liberated from state interference, traditional values, and dominant ideologies. In this they responded to ideas articulated in the 1938 manifesto Pour un art revolutionnaire (Towards a Revolutionary Art). Drafted by Andr├® Breton and Leon Trotsky at the Mexico City home of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, it called for an international front in defence of artistic freedom. While a part of this international community, and in communication with the global network of Surrealists, the Cairo group was also of its place, expressing local concerns and incorporating Egyptian motifs and symbols into their work.

CONVERGENCE POINT: MEXICO CITY

In Mexico City, as in other locations, taking up Surrealism meant grappling with the dual forces of internationalism and nationalism. Mexican Muralism and Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jos├® Clemente OrozcoŌĆÖs grand narrative murals had taken on an official government role since the Mexican Revolution (1910ŌĆō20). During the 1930s, however, the poets and artists of Los Contempor├Īneos (The Contemporaries), including Mar├Ła Izquierdo, distanced themselves from muralism and, along with Frida Kahlo, forged connections with Surrealism.

With its open-door policy, Mexico was a welcoming home to those fleeing totalitarian Europe. Including the political revolutionary Leon Trotsky (exiled from the Soviet Union), the circles around Kahlo and Rivera were internationalist, and it was through their encouragement that many Surrealists arrived in Mexico City. Further attention came with the work of poet C├®sar Moro, who organised the 1940 Exposici├│n internacional del surrealismo.

A core community of Surrealist artists who came together in Mexico City were women. In the particular case of Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, their friendship involved the study of MexicoŌĆÖs Indigenous cultures and archaeological sites. Influenced by occult and alchemical sources, these artists also infused Surrealism with feminism, magic, and natural forces.

11. ALTERNATIVE ORDERS

Mayo (Antoine Malliarakis) Coups de b├ótons 1937 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (D├╝sseldorf, Germany) ┬® DACS, 2022

While exploring dreams and summoning the unconscious to upset the status quo, Surrealism has also depended on forms of knowledge, patterns of belief, and ways of life outside urbanised modernity. These ŌĆśalternative ordersŌĆÖ, located through the research and practice of each individual artist, have the power to challenge established systems and spark the potential for acts of liberation.

Surrealist enquiry has benefitted from retrieving or uncovering the past, sometimes merging several unrelated traditions or positioning itself between them. For example, Kitawaki Noboru drew upon both the Taoist (ancient Chinese religion and philosophy) book of the I Ching, and German author Johann Wolfgang von GoetheŌĆÖs book on the theory of colour. For some, like Kurt Seligmann, the search has extended to magic and alchemy. While Y├╝ksel Arslan focused on the complete dismissal of existing forms as a way to produce his own work through a unique combination of materials. Through the power of fragmentation and juxtaposition, artists drawn to Surrealism across different places and times, have found ways to operate in new multidimensional spaces between cultures and eras.

AUTOMATISM

Surrealist automatism represents ŌĆö much like the harnessing of dreams ŌĆö a way to free the mind and challenge the rationalism of the modern world. Unconscious creation, like doodling, has been a catalyst for an array of artists working in related processes of improvisation. For example, a dynamic group of poets and artists in 1940s Aleppo embraced automatic techniques. As poet Urkhan Muyassar explained, they sought to free the ŌĆśmysterious momentsŌĆÖ of human creativity from a ŌĆśsuperimposedŌĆÖ reasoning in order to reach repressed thoughts, or ŌĆśwhat lies behind realityŌĆÖ.

Automatism has generated many inventive practices beyond line drawing. These range from Asger JornŌĆÖs use of paintersŌĆÖ tools to scratch away the surface of a work to Oscar Dom├ŁnguezŌĆÖs surprise compositions made through decalcomania, a technique in which two painted surfaces are pressed together and then pulled apart. As seen in the works shown here, automatism can capture the unguarded process of thought, bypassing the selectiveness and control of the conscious mind.

Surrealism Beyond Borders is on at ║┌┴Ž╔ń 24 February ŌĆō 29 August 2022